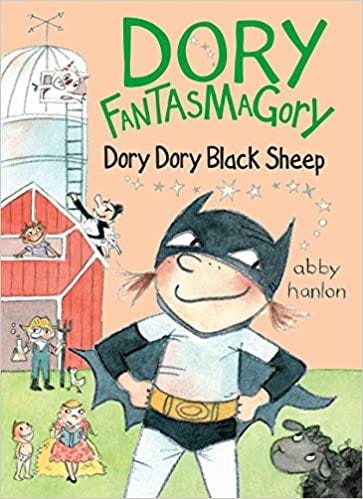

Abby Hanlon, Dory Dory Black Sheep

the pain of self-absorption & the value of the inner first person

“It’s like hugging, but more dangerous.”

As anyone who’s ever been, or been near, a child can tell you: children are self-centered. This sounds like an indictment (Does anyone want to know whether I feel like hearing Moana again?), but I mean it as a call for compassion. Because to be self-centered in the way of a child is to suffer exquisitely.

Squabbling parents; dying relatives; the defeats of far-off sports teams — these are all, when you’re a child, personal judgments rendered by a cosmos that happens to be headquartered in your bedroom. The megalomaniac’s cackling Mine, all mine! becomes the child’s wretched lament: Mine (oh God)…. all… (oh no) mine. My shirt is stained? I must be a fundamentally rumpled creature. My parents have gone out to dinner? They must be plotting to abandon me. Every child is the despotic ruler of a nation in crisis — the child’s face printed on the currency that’s being burned in the streets.

So: one job of the children’s book writer is to penetrate this dark and secretive kingdom and let some light in. You know those shameful thoughts? Those troubling body parts? We’ve all got ’em! Check out this spunky protagonist going through precisely what you’re going through!

Crafting an appropriately spunky protagonist, though, is trickier than it sounds. Overdo the brattiness — put a few too many Shut up!’s in her mouth, have her engage in some too-easily-emulated act of mischief — and you end up inspiring misbehavior rather than validating the stew of feelings behind it (these are the books that get barrages of one-star reviews from sorely disappointed religious-sounding readers). Err on the side of primness, however — outfit her with sins on the order of classmate envy and lollipop theft — and you leave the reader feeling bored and unseen.

No writer steers between these twin perils more expertly than Abby Hanlon. Her Dory Fantasmagory books — the best, and funniest, contemporary chapter book series I know — brim with authentic childhood turmoil. Their protagonist, Dory, pinches her older brother and then seethes with fury when he has the audacity to laugh. In a tantrum she locks herself in the bathroom and then, discovering that she can no longer work the lock, panics, screaming for help.

But the books are warm at the center. Dory is furious at her siblings — and then ecstatic when they include her in their games, dragging her around the living room by her feet. She is maddened by her parents’ obtuseness (Dory’s mom, when Dory requests a snack of cake, counters with yogurt) — but confides in them at bedtime her fear that her best friend may be sick of her. The books read as if written at the end of a tumultuous day (I’ll check on you in five minutes if you STAY IN YOUR BED!) that nevertheless, in the mellow glow of the hallway nightlight, reveals itself as having been somehow precious, hilarious, heartbreakingly evanescent.

The secret to Hanlon’s achievement — or anyway the secret that’s most clearly traceable to writing — has to do with her use of the first person.

The Dory books unfold explicitly within Dory’s head. Her imaginary world — full of monsters and villains and fairy godmothers — exists alongside the workaday world of teachers and cubbies and time-outs. For reasons of authenticity and coherence, the books need to be narrated by Dory in the first person. But — have you ever listened to a six year old tell a story?

So Hanlon places the book’s narrative voice not in Dory’s mouth but in her mind. “My two worlds swirl together like a chocolate and vanilla ice-cream cone. Real and unreal get all mixed up into one crazy flavor.” This is recognizably Dory’s image — but it’s rendered clear and coherent, stripped of the verbal stumbles and tangents that would clutter Dory’s actual, spoken explanation of her world.

In the third and quite possibly best book, Dory Dory Black Sheep, Dory races over to greet her best friend Rosabelle in the school yard.

“We take turns picking each other up. It’s like hugging, but more dangerous.”

Is there a parent who hasn’t stood wincing worriedly on the playground, watching children pick each other up? (My daughter bears a white scar behind one ear, relic of just such a greeting.) And is there a parent who hasn’t wondered why in God’s name kids can’t just hug each other on terra firma?

It’s like hugging, but more dangerous.

Here Dory explains it — and with an exactitude and economy that no child’s speaking voice could ever manage. The danger is precisely the allure. The impulses — toward affection, toward adventure — are so close, so energetically entwined, as to be nearly indistinguishable. The sentence (which obeys the old comedy dictum: place your funniest word last) has a delightful finality to it, as if it were the closing statement at a press conference.

And the sentence also — with its simultaneous transparency (so that’s why!) and opacity (but why is dangerous a good thing??) — neatly captures the brilliance of Hanlon’s method. What children say and do is often baffling, infuriating, mortifying to anyone even distantly related. What they think and feel, on the other hand, is nearly always relatable and surprising and heart-tenderizing, when you’re able to suss it out. By placing her narrative microphone in Dory’s frontal lobe, Hanlon makes her, and therefore children, fathomable — to their parents and, more importantly, to themselves.

When my daughter discovered Dory, the population of her inner world — that strange and worrisome territory — instantly doubled. I like to imagine her, thrilled at recognizing a fellow veteran of inexplicable terrors and joys and longings, racing over to pick Dory up. And I like to imagine further (going against all I know about children and balance and velocity) that they somehow stayed on their feet.

The Dory books are very well liked, even beloved, by my children. Reading them out loud, I recognized the understanding and realism with which Abby Hanlon writes about the dual worlds that children inhabit. Abby has clearly been able to, as Edward Eager once said, "access the child mind." :)

Eye-opening discussion about the layers of parental protection being peeled back and replaced by a child’s growing ability to care for themselves. Fascinating. I will buy her books today to read the author’s first person work.