“When the little man's back was turned, the big man snuck a needle-thin droplet of household cleanser into his water and watched the little man hallucinate all night long, tossing and turning, retching small pink piles into the corners of the cage.”

When you’re starting out as a writer, you imagine that what you really need — all that stands between you and a phone aglow with messages from the MacArthur and Nobel Committees — is an idea. If only you had a truly first-rate notion for a novel or a story (A woman gives up her family life in order to… A boy is walking to school when he discovers…), you’d be all set.

It’s therefore dispiriting, once you do manage to come up with an idea, to discover just how little you actually have. Because what you realize, over weeks or months of attempting to transport your idea to the page, is that, in order to become something worth reading, it will need to be chopped and shredded and subjected to all manner of pressure. Your initial idea may not — it very likely will not — even be recognizable in the finished product. You thought you were holding a meal; you were in fact holding a raw potato.

Ordinarily this transformation happens out of the reader’s sight. Only when the author informs us, in a charmingly candid interview, that her World War One epic started with an item she heard on the radio about malaria nets, are we able to glimpse, through the gourmet polish, the initial ingredient in all its unpromising grubbiness. But recently I came across an open kitchen. In Aimee Bender’s “The End of the Line” you have the rare opportunity to watch, sentence by sentence, as a writer kneads an idea into art.

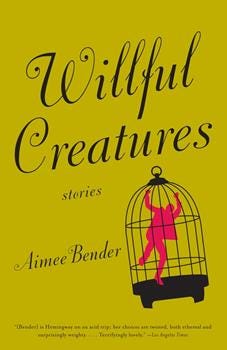

Bender writes mostly short stories — her best-known collection is The Girl with the Flammable Skirt — and she belongs somewhere on the shelf beside George Saunders (the angular sentences, the tenacious oddity) and Lorrie Moore (the nonchalant wit, the penchant for placing emotional trapdoors beneath the unsuspecting reader). “The End of the Line” is among the best and strangest things she’s written.

The idea of the story is: a man goes into a pet store and buys, as a pet, a little man. The little man lives in a little cage with a miniature sofa and miniature TV. A meal for him is a drop of whiskey and “a thread of chicken with the skin still on.” This — the image of the miniature man living a doll-sized life in the big man’s house — must have been what sent Bender to her keyboard in the first place.

So she must have been alarmed by just how short a distance this story-fuel carried her. By the end of the third or fourth page we’ve become accustomed to the setup (the greedy reader is no longer satisfied with the clever sub-conceits, e.g. the little man himself having an ant for a pet) and we’re demanding something new, something further.

“The two men got along for about two weeks. The little man was very good with numbers and helped the big man with his bank statements. But between bills, the little man also liked to talk about his life back home and how he'd been captured on his way to work, in a bakery of all places, by the little-men bounty hunters, and how much he, the little man, missed his wife and children.”

You can feel, in this passage, Bender picking up and discarding the crappy-Netflix-movie version of where the story might go — the little man teaches the big man some much-needed life lessons (maybe the little man is good not only with numbers but with romantic advice); the big man sets the little man free, microscopic tears of gratitude glistening on the little man’s cheeks.

Bender is too good, and too strange, to waste time with that. She must have sensed something promising in the darkness of the mechanics — the little man captured on his way to work, his separation from his family. Let’s press on that.

‘You're mine now,’ he told the little man. ‘I paid good money for you.’

"But I have responsibilities," said the little man to his owner, eyes dewy in the light. ‘You said you'd take me back,’ said the little man.

‘I said no such thing,’ said the big man, but he couldn't remember if he really had or not. He had never been very good with names or recall.

The story is now pulling up to a dark intersection. Behind us, nearly abandoned, is the story’s potential sweetness; the story has forfeited its kinship with, say, The Indian in the Cupboard. Ahead of us is… something more troublesome. But just how troublesome? Something in the reader is tightening apprehensively (a promising development, for a writer).

And then Bender steps on the gas.

“When the little man's back was turned, the big man snuck a needle-thin droplet of household cleanser into his water and watched the little man hallucinate all night long, tossing and turning, retching small pink piles into the corners of the cage.”

Oh! No matter how many times I read this sentence, it never fails to shock me. The grimly sober, torture-report language: household cleanser, hallucinate, retching. The precise and plausible sadism of that needle-thin droplet. And then those small pink piles — which, with their incongruous adorability (is this the daintiest vomit in literary history?), keep us at least partially grounded in the premise. This is still a doll-house world; it is also a world of genuine cruelty and suffering.

And now Bender really is home free. Whatever she does next (does the big man’s brutality escalate? does the little man try to escape?) can’t help but be interesting. She has treated her idea with the necessary cruelty — she has thrown it around, poked it, fed it strange chemicals — and it has, in the perverse way of ideas, responded not by abandoning her but by rewarding her. It’s metamorphosed. It’s not an idea any more. It’s a story.

I think Birds of America is Moore's best, although it's hard to go too far wrong. Agree re short stories and summer -- though I'm not obeying that wisdom in the least, currently reading (and enjoying!) Abraham Verghese's new doorstop on a beach vacation.

I know! It's brutal. And yet a very enjoyable (at least in the artistic sense) story