“If you don’t like scallops but have nonetheless read this far, you can substitute any firm-fleshed white fish fillets, skinned and cut into small pieces.”

The typical cookbook is the product of — the long-reduced essence of — one person’s sensibility. This gives the typical cookbook a slightly claustrophobic air. Molly Baz, for instance, is a wonderful cook and writer, but by the time we have pickled for a couple of hundred pages in not just her verbal tics but her characteristic flavor combinations and her graphic design choices — we feel a strong urge to fling open the window.

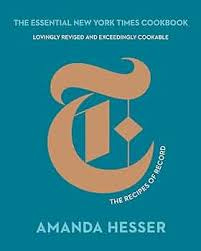

The greatness of The Essential New York Times cookbook is that the window is already open. And Amanda Hesser — who is listed as the book’s author but is really something more like its presiding spirit — spends its 900-plus pages expertly fluttering us in and out of kitchen after kitchen, decade after decade, century after century, lingering just long enough to teach us a certain recipe or technique before moving brightly on. Here is a 1958 recipe for Jellied Strawberry Pie a few buildings away from a justifiably famous Purple Plum Torte from 1983. Here is J. Kenji Lopez López-Alt’s compulsive procedure for Perfect Boiled Eggs (which take all of eight minutes) a few pages away from Mollie Kaizen’s Amazing Overnight Waffles. There is something here, many somethings here, for the cook of every inclination, every level of expertise, every level of access to or interest in this or that farmer’s market darling.

And the miracle of the book — the thing that makes it more than the world’s largest and most overstuffed bin of handwritten index cards — is the lightness with which Hesser manages to bind it all together. What she’s made, essentially, is an anthology. And the crucial work of the anthologist is of course the choosing (“Entire cookbooks could be made of the macaroni and cheese recipes in the New York Times archives. They are numberless, going back to ‘Macaroni au Gratin’ in 1904…”)

But the art of the anthologist — the thing that gives an anthology its human warmth — is how she ushers you from one selection to the next, the voice in your ear that accompanies the hand on the small of your back. And Hesser happens to have a voice that is funny, succinct, opinionated — and deeply, blessedly practical.

About Clambake in a Pot she writes: “A clambake without sand in your food.”

About Eleven Madison Park Granola:

The Times received feedback from readers on what they deemed an excess of salt called for in this recipe. I am going to diplomatically declare those readers wrong.

To the end of the plum torte recipe (which the paper had to run twelve times, before everyone had easy access to the archives) she affixes a handful of rapturous, idiosyncratic reader letters, one of which ends with the sentence: “And yes, I did laminate it!” To which Hesser adds, with brackets hers: “[Presumably, the recipe, not the cake.]” A good cook, we’re perpetually told, is forever tasting what she’s cooking — and Hesser, as in this joke about lamination, is forever tasting what she’s just written, responding to it, squeezing a lemon over it when it’s gotten out of balance.

My favorite instance comes in a recipe I doubt I’ll ever cook: Sea Scallops with Sweet Peppers and Zucchini. After a short paragraph extolling scallops as an alternative to yet another sautéed chicken breast, Hesser writes:

If you don’t like scallops but have nonetheless read this far, you can substitute any firm-fleshed white fish fillets, skinned and cut into small pieces.

That miniature joke — nonetheless read this far — is the essence of Hesser’s charm (what was I doing following along on this particular errand?), and a clear view of the way that her voice, a small delicious nubbin of vitality, inhabits this massive whorled shell of a book.

One of the first pieces of prose ever to truly move me (I was twelve years old, and an easy mark) was Mr. Antolini’s speech to Holden in The Catcher in the Rye:

“You’re not the first person who was ever confused and frightened and even sickened by human behavior… Many, many men have been just as troubled morally and spiritually as you are right now. Happily, some of them kept records of their troubles. You’ll learn from them — if you want to.”

A cookbook like The Essential New York Times Cookbook is at its heart a record of human troubles and our collective attempts to overcome them. How do we take this stuff we’ve been granted — these unpromising knobby plants and mysterious animal-bits, this appetite and these clumsy hands — and make the best of it?

We may not like scallops (we may be one of the apes who linger queasily toward the back of the pack while the lead ape pries open a shell and scrapes something gelatinous from its interior), but because we are in good company, because we too are stuck in this baffling wilderness, we stick around. We read on.

What an engaging review of a large collection of recipes and the text that accompanies them. I'm going to have to check this one out to see if the ratio of recipes I might try (I love scallops) vs recipes I'd never try (anything where beets are the main ingredient) is greater than 1. I'm retired now so I have time to bake and cook, and to enjoy what I make (or to toss it and try again).