“She was in Argentina for the year, working with the architectural firm that Mr. DeCuervo’s father had started.”

A recurrent predicament for a fiction writer:

Here you are, telling your story — let’s say it’s about a boy and his grandmother going out for ice cream — and you need, in order to make the story work, to tell a different, older story: about how, say, the grandmother, during her first pregnancy, lost her taste for ice cream and worried it would never come back.

How, structurally, do you manage this? How do you move the reader off of the main highway of narrative without resorting either to the teleportation of a line-break (effective but jarring) or, much worse, to the construction of a rickety and hideous bridge (While they stood waiting for the light to change, her mind drifted to a series of long-ago summer evenings…)?

I’ve seen good writers — Anita Brookner-good — reduced by this challenge to what I think of as the Zack Morris: having your character pause, stare off into the distance, and then experience a memory as distinct (we know it’s a memory because of the haze around the perimeter of the screen) as a visit to the dentist.

The problem with this isn’t that it’s false (though it is false, memory being not so much a place you visit as a detritus you carry, a layer of barely legible receipts and inexplicable pebbles at the bottom of your tote bag) — the problem is that it’s inelegant. And inelegance pops the reader out of story-reading mode and into story-critiquing mode. What we need here is a means of moving the reader between the present and the past so smoothly that she barely notices it’s happening — what we need here is a loop ramp.

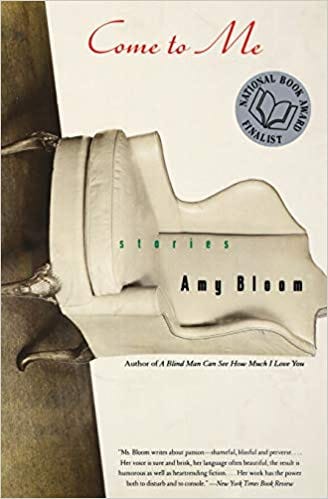

And the preeminent loop ramp engineer of our time happens to be Amy Bloom. Watch how she does it in her great story “Love is Not a Pie.”

The story begins like this:

“In the middle of the eulogy at my mother’s boring and heart-breaking funeral, I began to think about calling off the wedding.”

So that’s the present situation, the highway: a woman at her mother’s funeral, thinking of backing out of her engagement.

The narrator, her sister Lizzie, and her father stand greeting the mourners. And then, one page into the story, here comes the exit sign. Someone named Mr. DeCuervo comes in, and the father reacts… interestingly:

“[He] went charging over to Mr. DeCuervo, wrapped his arms around him, and the two of them moaned and rocked together in a passionate, musicless waltz. My sister and I sat down on the couch, pressed against each other, watching our father cry all over his friend, our mother’s lover.”

Our mother’s what? Who is this, again, that the father is waltzing and weeping with? The spike of readerly curiosity (like the little spike of preoccupation a driver feels when changing lanes to exit an unfamiliar highway) briefly monopolizes our entire mental screen. So we aren’t much troubled — we don’t even necessarily notice — when, in the next sentence, we are suddenly decades in the past.

“When I was eleven and Lizzie was eight, her last naked summer, Mr. DeCuervo and his daughter, Gisela, who was just about to turn eight, spent part of the summer with us at the cabin in Maine.”

And for the next eleven pages, we stay there, back in the Maine of the narrator’s childhood. We learn all about the Mr. DeCuervo, and Gisela, and the narrator’s parents. Bloom leads us at, at just the right speed, toward the long-ago night that will untangle our earlier bewilderment.

But for the reader who happens also to be a writer, the story’s suspense isn’t merely narrative — it’s technical: how is Bloom going to get us back to the funeral? It’s one thing, and not a small thing, to get us off of the highway and into the thickly peopled town of the past. It’s another to get us back onto the highway, away from this town in which we’ve grown so comfortable, this town in which we’ve spent eleven of the story’s twelve pages, and to do so in a way that convinces us that the highway of present action was busily humming with traffic the whole time we were gone.

Well, behold this marvel of engineering:

With the Maine summer business accomplished, and only a few pages left in her story, Bloom begins steering us gently back toward the present.

“The next, summer I went off to camp in July and wasn’t there when the DeCuervos came…”

“We saw them a little less after that…”

The highway traffic is becoming audible.

And now here comes the ramp.

“Gisela couldn’t come to the funeral. She was in Argentina for the year, working with the architectural firm that Mr. DeCuervo’s father had started.”

What I love about this particular loop ramp is the trickiness of its angle. The actual merge is accomplished in the first sentence — Gisela couldn’t come to the funeral (oh right, the funeral!). But it’s the second sentence, with its just-distracting-enough flurry of detail (Argentina! I didn’t know Mr. DeCuervo’s father was an architect!), that keeps us from being jarred by the transition. Bloom knows that readers ought, in certain circumstances, to be treated exactly unlike novice drivers: talk to them while they attempt perilous lane changes! Distract them with colorful irrelevancies!

Before they know it they will be back on the highway, their trunks loaded with goodies from town, their engines contentedly purring.

I always love your posts, but this one speaks so brilliantly to exactly the feat I'm trying to accomplish over and over again in book-length form (a scientists's biography masquerading as narrative non-fiction) so I just wanted to say thank you. THANK YOU.

This is a great breakdown of how structure is looming, but enacted at the sentence level.