“Even as I held it, it sunk its teeth into my hand and bit me.”

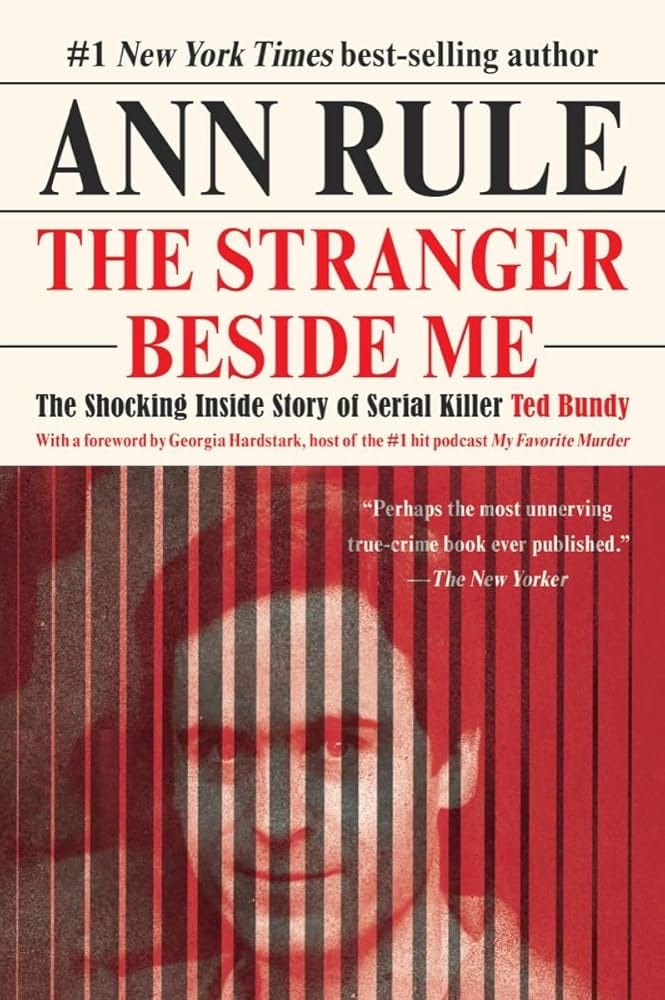

Ann Rule’s The Stranger Beside Me, the little battered paperback that has been radiating evilly on my bedside table, is an object of extraordinary power. Which isn’t to say that I think you should read it. A downed power line is also an object of extraordinary power; so is a rabid fox.

For the couple of weeks I spent in the terrifying, bewitching company of Ted Bundy, I kept asking my wife, plaintively, whether I should put the book down. Reading it was doing things to my dreams; it was making me look at my daughter with an even-more-acute-than-usual feeling of fretful helplessness. But I read to the end. I needed to see that Bundy ended up in prison (a prison he couldn’t escape, finally). And now I think I’ll put the book out on my stoop, perhaps sealed in a Biohazard bag.

Ann Rule — who went on to become one of true crime’s most prolific and esteemed practitioners — was just starting out when she wrote it. The circumstances that brought it about must count among the strangest coincidences in publishing history. Rule, a divorced mother patching together a living as a freelancer, was hired to write a book about a series of women who had disappeared in the Pacific Northwest. When the police finally settled on a suspect (the killer, whoever he was, was horrifyingly good at concealing his tracks), he turned out to be Rule’s dear friend Ted. They’d worked together at a suicide hotline, where Ted had stood out mainly for his brilliance and his “old-world gallantry” (he insisted on accompanying Rule to her car after long shifts). Now her book was not only going to be about the hunt for a monster — it was going to be about her slow (slooooow) acceptance of the fact that the monster was to be found in the cubicle next door.

This means that the book is a study of not one but two disturbed minds. The first mind of course is Bundy’s. He was a killer of spectacular, inhuman cruelty. Reading about him you search desperately for some explanatory event, some piece of biographical or biological data, that might place him at a safe distance from the rest of us. But little emerges. He appears to have had a sad but non-brutal upbringing. He was handsome and athletic — and charming enough to convince more than one romantic partner to overlook the matter of his murder convictions (even while incarcerated he managed to get married). He could, more than one bewildered observer points out, have become a successful politician or trial lawyer.

The second disturbed mind in the book belongs to Rule herself. She persists in believing in the possibility of Ted’s innocence long past the point of absurdity. (When fibers from Ted’s jacket and from the floor of his van are found on one of the victims, she solemnly qualifies the evidence: “Extremely probable — not absolute.”) She writes compassionately about the women — particularly Ted’s long-suffering girlfriend Meg — who were blinded to Ted’s evil by loyalty and a kind of emotional sunk cost fallacy. And yet she can’t quite keep herself from joining their ranks.

But what makes the book fascinating — what makes it more than just a particularly lurid episode of Dateline — is the way that Rule’s unconscious keeps shouldering her more credulous self aside at the keyboard. Two-hundred pages into the book, after countless extremely probable suggestions of Bundy’s guilt, Rule records a disturbing dream.

She’s standing in a parking lot, and:

One of the cars ran over an infant, injuring it terribly, and I grabbed it up, knowing it was up to me to save it…

In the dream Rule runs for help, but everyone turns her away. Finally she puts the baby in a wagon and drags it miles to the nearest emergency room. There too her pleas are met with indifference:

“But it’s still alive! It’s going to die if you don’t do something!”

“It’s better. Let it die. It will do no any good to treat it.”

The poor baby seems to be doomed.

And then I looked down at it. It was not an innocent baby; it was a demon. Even as I held it, it sunk its teeth into my hand and bit me.

Rule will insist that this could all just be a dreadful coincidence for another hundred pages, but from this dream on we know that she is battling a mighty inner tide. Ordinarily I praise a writer for her conscious, careful effects, but here I want to celebrate the crude power of Rule’s sleeping mind. Even as I held it, it sunk into teeth into my hand and bit me. What a great, compact image that demonic biting baby is! What a flare sent up from the depths!

The theme of the book — the theme of nearly all true crime — is that we are in more danger than we think. Unfathomable evil might lurk behind the placid face of any neighbor, any friend. But with this dream, and with all the many women throughout the book who don’t go with Bundy, who report seeing an indescribable something in his eyes that warned them off, Rule points us toward a kind of consolation. There aren’t just predators lurking out there in the dark. There are protectors too. They smuggle us their wisdom in the form of shivers down the spine, aversions to walking down certain streets, dreams. They are friends worth heeding.

This book bored a hole in my brain. I’ve never read a more unnerving portrayal of evil and its unlikely seductions. I once owned a copy, but like you I could not keep it.

Great summary. I particularly liked "They smuggle us their wisdom in the form of shivers down the spine, aversions to walking down certain streets, dreams. They are friends worth heeding." It took me a while to pay attention to similar "vibes" because I'm the type of person who tries very hard to operate using logic but, as I got older (more experience and more maturity) I learned that there was a reason for these physical warnings that didn't come from the logical part of my brain. I began to pay careful attention to them and to heed them. By the way, while I absolutely love murder mysteries I do not like true crime and would never read this book. I already know that horrible humans exist (mostly men).