“There!”

Board books are the single-celled organisms of literature. With their sparely decorated pages and their frequent lack of all character and story they seem, many of them, to have the blunt insentient eternality of rocks or puddles. My First Shapes. Things That Go. These books don’t set out to provoke thought, and they rarely stumble into it.

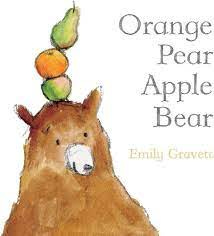

But place the right one under a microscope and you can discern, amidst the blankness and the bunnies, the wriggling rudiments of the mechanisms that more complex literary organisms, further up the evolutionary tree, will take up and make great use of. Emily Gravett’s Orange Pear Apple Bear — the only board book that I’ve insisted on keeping, years after my daughter has moved on — contains, in its twenty-two pages, a gorgeously formed ancestor of the narrative arc. Pay particular attention to the loveliness of the ending.

The book establishes its rules in its opening pages. Orange. Pear. Apple. Bear. Each gets its own page, and its own colored drawing. These are the dramatis personae.

And once Gravett has introduced them, she begins to recombine them. Apple, pear shows a pear perched atop an apple. Orange bear shows, more intriguingly (note the absence of a comma between Orange and bear), that our familiar brown bear has now turned orange. The elements aren’t just being rearranged; they are being hybridized.

Soon we have an Orange pear (simple enough) and an Apple bear (the bear, to her own evident confusion, takes on the green and red coloration of the apple). This is the part of the book that screenwriting guides refer to as the promise of the premise — we now know how the story’s universe works, and for a happy while we sit back and watch the gentle rhymes and the subtleties of punctuation rearrange the cosmos. Apple, orange, pear bear yields a pear-shaped bear holding an apple and an orange. Orange, pear, apple, bear gives everyone back their bodily integrity: the bear is balancing the three fruits on her head.

But a subtle tension begins to build. Orange, bear shows the bear guiltily/proudly holding up a plate on which only the orange peel remains. Pear, bear has her tossing the core of the decimated pear toward her open mouth. The bear — who has always been the story’s prime mover — is discovering her proper relation to the other characters: she is going to take them into her being the old-fashioned way. A certain vicious, irresistible logic sets in.

By the time she’s devouring the apple (Apple, bear), we feel the ending approaching, the way that a backstroking swimmer feels the nearness of the wall and begins to extend her fingertips in anticipation. But how is Gravett going to manage it? She’s been ruthless in her adherence to the rules: the only words she’s allowed herself have been orange, pear, apple, and bear. But those elements are now vanishing. Will she end with just Bear, solitary and triumphant? Isn’t that a bit Darwinian? She’s running out of story possibilities, and running out of words to describe them. We have only one page left, and the situation — at least for those who’d grown attached to the fruits — is bleak.

And this is when Gravett manages the miraculous helicopter airlift that is a perfectly executed ending.

She shows the bear walking cheerfully away from her collection of cores and peels, accompanied by the solitary word:

There!

A fifth word! The book’s four walls drop away. The word is surprising (thanks to its novelty) and inevitable (thanks to its story-logic and rhyme). This is the There! of an artist putting the finishing touch on a canvas, or of a parent wet-wiping the last smear of melted chocolate from a toddler’s cheek. It signifies both pleasure and completion. The word belongs firstly to the bear; she has had her fun, and had her fill. But it belongs also to Gravett — who, I’d be willing to bet, was as surprised and delighted by her book’s ending as we are.

Good endings aren’t created; they’re discovered. They’ve been lurking all along inside the ingredients we’ve been playing with — and somehow beyond them too. You can recognize them by their hilarious audacity. They violate the bounds you’d established and show you the absurdity of those bounds at the same time. They hand you the remains of the snack you carefully packed — the squeezed-out juice-box, the torn Goldfish bag — and race off happily into the playground, leaving you to marvel and tidy up. They upend your plans and laugh about it. They’re obnoxiously, ecstatically alive.

I always look forward to your emails and today's made me smile. Thanks.