Franz Kafka, "The Judgment"

unvisited galleries & improv comedy

Hi everybody!

This is going to be the last One Sentence for a while. Fully intoxicated by the promise of September (the thinking person’s New Year), I’m hoping to focus on fiction-writing for a bit.

Please do keep the recommendations coming, though, and I’ll see you back here when I read something so good that I can’t bear not to blather about it.

Thank you, truly, for reading,

Ben

“‘I know your friend very well.’”

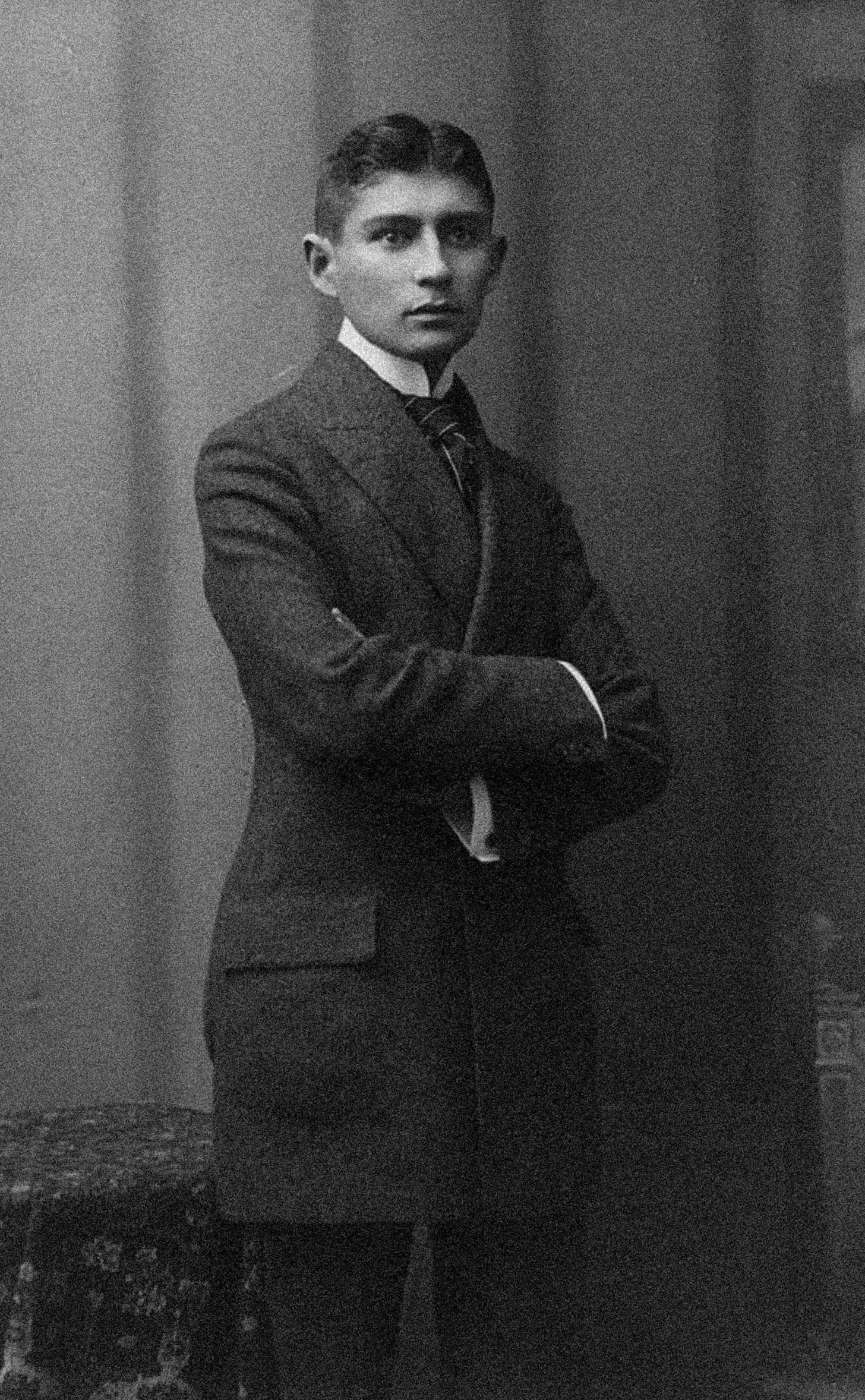

Reading Kafka can feel like interviewing a celebrity whose handlers and hangers-on won’t leave the room. His work is so encircled by academics and obsessives, by portraitists and publicists, that you can barely make out the prose itself. You want to meet Franz — the lean, neurotic insurance agent, chuckling to himself while he scribbles at his desk in the middle of the night — and instead you keep meeting KAFKA — the modernist icon, the living souvenir.

Two things, I’ve found, help facilitate a private encounter with the man himself:

1. A proper translation — which is, to my tastes, Michael Hofmann’s. Hofmann’s Kafka is less dour and imposing than Willa and Edwin Muir’s. Every essay about Kafka eventually recounts the story that Kafka and his friends would, when Kafka read his stories aloud, laugh until they fell out of their chairs. In Hofmann’s translation you understand why.

2. A meeting place away from the tourist sites. When you read The Trial or Metamorphosis you are so self-conscious, so aware of the millions of readers who have stood where you’re standing, thinking their no doubt far-superior thoughts, as to be semi-paralyzed. Much better to rendezvous in the comparatively unvisited gallery of, say, “The Judgment.” (And then, once you’ve spent a bit of time with Franz, he’ll sneak you, giggling, into more famous works — the throngs won’t even notice you.)

“The Judgment” — a sixteen-page story written, unbelievably, in a single night in 1913 — is a masterpiece in the original sense: before he wrote it, Kafka was a promising, eccentric talent; afterward he was one of the indispensable writers of the century.

The story opens with Georg Bendemann, a young and conscientious businessman, writing a letter to a friend. This friend (“dissatisfied with his prospects at home, [he] had abruptly lit out for Russia several years ago now”) is an expat — and no more content in Russia than he had been at home.

“What could you say to a man like that, who had obviously lost his way, whom you might sympathize with, but could do nothing to help? Should you advise him to come home, to take up his old life here, pick up the threads of his former friendships…”

Georg frets and ruminates: the friend didn’t respond especially well when Georg wrote him, a couple of years ago, about the death of his mother. Maybe Georg should write to him about business? But maybe the recent success of Georg’s business (which Georg’s father is in the process of handing down) will make the friend feel even worse about his own failings? And does Georg dare tell him his truly momentous news — that he’s gotten engaged to a woman named Frieda? (And would Georg then have to invite him to the wedding?)

So far, so satisfying. The psyches are well-rendered, the situation is compelling. But you get the sense that this could have been written by Chekhov or Maupassant. Which is not, of course, an insult. But neither is it Kafka’s final destination. To this point in the story, he hasn’t emerged from the chrysalis of realism.

Here are the first wriggles:

Georg puts the letter in his pocket and goes into his father’s room. Georg hasn’t, apparently, been going into his father’s room much lately — they see each other all the time at work, and besides, Georg is so busy these days with Frieda. The prose, recounting this set of facts, acquires a slightly heliumized tone of anxious self-justification. So what if his father happens to be a widower? It’s not Georg’s fault that his father just sits here in the dark!

“‘Ah, Georg’ said his father, and he got up to greet him. As he did so, his heavy dressing-gown fell open, and the flaps of it fluttered around — ‘what a giant of a man my father still is,’ thought Georg to himself.”

We sense that something about Georg’s father — and about Georg’s relationship to his father — is, to use the technical term, off. Isn’t that open dressing gown a little creepy? And isn’t Georg a bit old to be quavering at his daddy’s bigness?

In any event, the two of them talk — Georg says he’s gone ahead and told his Russian friend about his engagement; his father harrumphs — and we think: OK, more psychological intrigue, more short story 101.

But then something strange happens. Georg’s father, in the midst of an indignant speech (he’s clearly bothered by Georg’s engagement, and maybe things aren’t going so great at work after all) says,

“‘But while we’re on the subject of this letter, do let me beg you, Georg, please do not deceive me. It’s a detail, it’s barely worth losing one’s breath about, so why deceive me? Do you really have this friend in Petersburg?’”

To which we — and Georg — say, Huh? But Georg’s huh is not, it turns out, exactly our huh.

“Georg stood up in some confusion. ‘Don’t let’s talk about my friends. A thousand friends are no substitute for one father.’”

Wait, so was Georg making up his friend in Petersburg? Why is he acting so guilty and weird?

You need to rest more, Georg tells his father, lapsing suddenly into caretaker mode, slightly frantic. We’ll move you into a brighter room. You can have my room. You can even have my bed.

His father responds feebly, bafflingly (“‘You don’t have any friend in Petersburg. You were always a practical joker…’”) and Georg undresses him, grimacing guiltily at his unclean underwear. Then Georg scoops up his father in his arms — this father who was, two pages ago, such a giant of a man — and carries him to bed.

“ ‘Everything’s fine,’” says Georg, “‘you’re properly tucked in.’”

At this moment in the story we’re trembling on the precipice of a handful of irreconcilable meanings. Maybe this is a story about a young man who has, unaccountably, invented/hallucinated a friend in Russia. Or maybe this is a story about a deranged and declining father.

Or maybe our understanding of the story is about to be kicked over like a plywood backdrop.

“‘No!’ shouted his father, in such a way that his answer collided with the question, threw the blanket back with such strength that it seemed to float for a while in mid-air, and stood upright on his bed. With one hand he supported himself lightly on the ceiling. ‘You wanted to tuck me in, sunshine, I know that, but I’m not buried yet. And even if it’s with my last remaining strength, I’m still enough for you, more than enough for you! I know your friend very well. He would have been a son after my own heart. That’s why you strung him along all those years. Why else? Do you imagine I didn’t weep for him?’”

This is the moment — the masterpiece within the masterpiece — when Kafka leaves the chrysalis behind. Because it turns out that Georg’s father never doubted the friend in Petersburg’s existence — the father knows him very well! The friend is like a son to him! The father was faking all along, just as he was faking his infirmity!

And poor Georg — who we know by now won’t deny or question a thing — just stands there and stares, terrified by his father’s sudden radiance, caught out to the marrow of his bones.

This reaction of Georg’s — a radical and slightly demented readiness to assimilate new information (particularly when that information comes with a side order of shame) — is the essence, and genius, of Kafka’s method. There’s a well-known and chipper-sounding rule of improv: Yes, and. Whatever one performer proposes (Here we are on the moon! Look, it’s raining cabbages!) the other takes up and expands on. In Kafka’s fiction — from this moment on — the governing principle will be Yes, and’s delinquent twin. Premises will be rewritten on the fly; durable-seeming relationships will be transformed; the compass of a character’s intentions will swing wildly. Unease and a certain bewildered indignation will be the only constants. Kafka has less in common with the moody moderns with whom he’s always lumped than he does with the comedian Tim Robinson, whose I Think You Should Leave Kafka would, I’m certain, have recognized as an heir.

When you do finally meet Kafka — away from his handlers, in a private room — you’ll find him clapping defiantly off the beat of his story’s music. His clapping will (depending on your temperament, depending on the story) strike you as funny, or weird, or confusing. But it will also strike you, in a deep and initially unplaceable sense, as familiar, almost eerily so. He isn’t clapping to the music, you’ll eventually realize; he’s clapping to the beat of your own guilty and senseless heart.

Have a good writing trip. Looking forward to your reading return.

Don’t go!! I always look forward to your exquisitely finished analyses. Your writing style makes one feel hungrily excited for the next descriptive sentence.