“Some nights he sat up late on his front porch with a glass of Jack and listened to the trucks heading south on 220, carrying crates of live chickens to the slaughterhouses — always under cover of darkness, like a vast and shameful trafficking — chickens pumped full of hormones that left them too big to walk — and he thought how these same chickens might return from their destination as pieces of meat to the floodlit Bojangles’ up the hill from his house, and that meat would be drowned in the bubbling fryer by employees whose hatred of the job would leak into the cooked food, and that food would be served up and eaten by customers who would grow obese and end up in the hospital in Greensboro with diabetes or heart failure, a burden to the public, and later Dean would see them riding around the Mayodan Wal-Mart in electric carts because they were too heavy to walk the aisles of a Supercenter, just like hormone-fed chickens.”

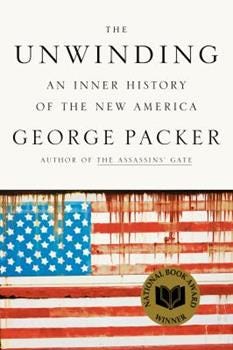

The first time a friend recommended The Unwinding was at a California wedding. We were on a long and lovely hike before the ceremony, and my friend was recounting for me Packer’s disconcerting thesis. Every couple of generations, Packer/my friend argued, America — its fabric frayed by economic or racial or political contradictions — goes through a rending crisis. The Civil War, the Great Depression. The sort of thing that inspires historians to haul out the capital letters.

And we were now, Packer/my friend went on, just on the cusp of such a crisis. Economic inequality, the racial backlash to Obama’s presidency, various political and social trends decades in the making — they’d been tearing away at what held us together and we were down now to the thinnest of threads.

Inspired by a certain wishful optimism, and perhaps the loveliness of the vineyard-covered hills around us (some of which, yes, were on fire), I expressed my doubts. Couldn’t you look at the great tangle of American history and imagine onto it any pattern you wanted? And even if we were fated to live through some sort of disaster, we’d already been through the financial crisis, and before that 9/11. Enough already, was my basic take. Let’s talk about Game of Thrones.

On Sunday we flew home, and on Tuesday Donald Trump was elected president.

So: when, years later, I finally forced myself to pick up The Unwinding, I was ready to be scorched by the flame of prophecies unheeded. I expected a pummelingly correct op-ed that went on for five hundred pages. What I found instead was something much stranger — a sober cousin to an oral history, a work less of prophecy than of portraiture. My friend hadn’t misrepresented it, exactly — the introduction does allude to the regular “unwindings” that have punctuated American history — but the bulk of the book doesn’t argue anything; it merely presents, in patient and meticulous prose, a handful of American lives, ordinary and deeply un-. And yet it functions as a powerful foreboding-generation device. As Packer writes of Raymond Carver: “in the silences between words a kind of panic rose.”

The book is structured as a series of fractured profiles — of factory workers, celebrities, entrepreneurs, politicians, all broken apart and reassembled with Studs Terkel-ish care. One of Packer’s favorite profilees — and the one who best demonstrates the book’s alarming power — is a North Carolinian entrepreneur named Dean Price. Price comes from generations of tobacco farmers (“They all had Scotch-Irish names that fit neatly on a tombstone: Price, Neal, Hall”), and for a while we watch him bounce around the Bruce Springsteen end of the American experience — working in factories, drinking too much, dreaming of greatness. He comes to own a gas station/convenience store, and eventually he becomes interested in alternative fuels — the term “peak oil,” encountered on a website called “Whiskey and Gunpowder,” strikes him with trajectory-altering force. It also (as too deep an acquaintance with the world of peak oil will) turns him into something of a crank.

Watch how Packer, in a single sentence, places us inside the acrid confines of Dean’s skull:

Some nights he sat up late on his front porch with a glass of Jack and listened to the trucks heading south on 220, carrying crates of live chickens to the slaughterhouses — always under cover of darkness, like a vast and shameful trafficking — chickens pumped full of hormones that left them too big to walk — and he thought how these same chickens might return from their destination as pieces of meat to the floodlit Bojangles’ up the hill from his house, and that meat would be drowned in the bubbling fryer by employees whose hatred of the job would leak into the cooked food, and that food would be served up and eaten by customers who would grow obese and end up in the hospital in Greensboro with diabetes or heart failure, a burden to the public, and later Dean would see them riding around the Mayodan Wal-Mart in electric carts because they were too heavy to walk the aisles of a Supercenter, just like hormone-fed chickens.

Is that not a miserable masterpiece? The sentence seems as if it might roll on forever — a cargo train you can only helplessly watch clatter by from behind your windshield. The language is plain, the structure is straightforward, the vision is pitiless. The brutal mini-scenes pile up until you’re begging for it to end; and then it does, with a flourish (just like hormone-fed chickens) that’s like a curtsy at the end of a mugging.

There are mental illnesses characterized by insufficient clarity — memory slippage, murk, failures to comprehend. And then there are mental illnesses characterized by excessive clarity — yes, things really are that hopeless, but you aren’t supposed to have it in mind all the time. Packer’s sentence, with its barely contained contempt and its uncontainable despair, captures a mind incinerating in its own clarity. It’s a cruelly perfect rendering of what happens when the pen light of attention is replaced by a floodlight, when the world in its hideous coherence seems to stand naked before you.

And it’s a mini — or not so mini — demonstration of what Packer is up to in this frightening and necessary book. He’s our national Ghost of Christmas Past and Ghost of Christmas Present. And he’s doing such a chilling and thorough job of it that he’s rendered the Ghost of Christmas Future superfluous.

I am a member of a book club and a writing club. I am going to form a Writers Book Club to examine the authors written about in this newsletter. I am sure we will all become better writers and readers and enjoy it more than studying via an MFA. Keep 'em coming!

I have become a loyal reader of this newsletter (I love waking up to these!) and this is one of my favorites so far. I read and loved this book and, in addition to giving me another dimension on which to appreciate it (like an amateur jazz listener, I must have felt the effect of Packer's literary techniques even if I hadn't noticed or understood them), this piece also provides a much better description of the book than I've ever come up with. Whenever I've recommended it, it's taken me waaaaaay too many words to describe what, exactly, it is that I'm recommending. "A series of fractured profiles," "a miserable masterpiece," "a mind incinerating in its own clarity," "a cruelly perfect rendering," "The sort of thing that inspires historians to haul out the capital letters." Yes, yes, yes, yes and yes!

This article so eloquently captures the gist and feeling of the book's vignettes... and how ironic that such concision and precision is found in a review of an excessive and effective run-on sentence!