“It was like waking up to discover you’ve drifted into the wrong lane and now traffic was coming straight at you, and there was no time, no time.”

Every artistic endeavor, however virtuosic, however noble, flirts with absurdity. I’m going to spend a couple of years obsessing about how best to describe the doings of a person who doesn’t exist. Sound like a plan?

Novelists (and actors, and comedians, and musicians) do their best not to let this feeling become crippling, but it never goes away entirely. All it takes is a fruitless morning at the keyboard and the doubts come geysering forth. What exactly is it that we’re doing here? Isn’t this embarrassing? Wouldn’t I be better off putting away these props and applying to law school?

In most cases the questions recede. A few chapters into writing a book there is only the book; the broader endeavor, in all its cosmic ridiculousness, ceases to register. In certain rare instances, though — and these, of course, are the ones we don’t tend to hear about, their participants being too busy with law school — the absurdity refuses to be ignored. It crouches unbudging by the keyboard, stinking and snickering from the first tentative words until the last miserable period.

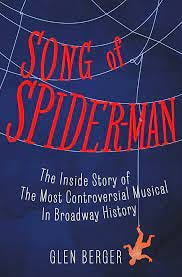

In Song of Spider-Man, a memoir by the playwright Glen Berger, we have an account (gruesomely detailed, queasily honest) of one such case. Berger’s book tells the story of his years working on the famously disastrous 2011 musical, Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. And Turn Off the Dark didn’t just flirt with absurdity — it stared deep into absurdity’s eyes, took its hands, and married it.

I should say up front that this is not the type of book I usually read. I’m somewhere between indifferent and hostile to: Broadway shows; showbiz memoirs; and the entire ever-expanding Spider-Man universe. I couldn’t tell you who Norman Osborn is or what a dramaturge does. I wouldn’t have gone to see Turn Off the Dark if it had been good and playing across the street, and I certainly never thought of going to it, as a great many people apparently did (more than two million, according to a still-wounded Berger), as a kind of voyeuristic lark.

But as a connoisseur of artistic failure, I found Song of Spider-Man irresistible. I read it in three days, recounting its grisly details to friends, racing to YouTube to revel in the chaos. There’s always been a ravenous audience for memoirs recounting horrific ordeals — the savage, drug-addled childhood; the high-seas disaster. Song of Spider-Man is my Endurance; it captures the nightmare of making a work of art as well as any book I’ve ever read.

Song of Spider-Man works because it has precisely the thing that Turn Off the Dark catastrophically lacked: a good villain. That villain, in Song of Spider-Man, is Julie Taymor — she of the MacArthur Genius grant and the multi-billion dollar Broadway resume. She promises Berger ever-lasting glory (he has, to that point, been toiling Off-Broadway) and she delivers him a nervous breakdown.

In the popular conception of Turn Off the Dark, what did it in were technical mishaps. Pitiless contraptions crushing actors or leaving them dangling over captive crowds, night after woeful night. But Berger makes clear that what actually did the show in were artistic mishaps, and one in particular — the decision to graft onto the standard Spider-Man story (boy, girl, spider-bite) the myth of Arachne.

Berger explains:

“Arachne was an artist so talented, and so intoxicated by her talent, that she refused to humble herself before anyone, even the goddess Athena. Ovid narrated in his Metamorphoses that when Arachne mocked Athena in a weaving contest, the irate goddess destroyed Arachne’s tapestry. In response, Arachne hanged herself with one of the tattered remnants of her own work. But! Athena didn’t allow Arachne to die. Instead, she transformed the girl into the world’s first spider.”

The ordinary mind, encountering this hunk of mythology, might think, Huh. That’s kinda neat. Doesn’t have much to do with Spider-Man, though. Back to writing leaps from skyscrapers!

But Taymor’s mind is, insistently, not an ordinary mind. It’s an artist’s mind. And that can mean The Lion King, with its ingeniously simple sets and its elegant costumes. Or it can mean Arachne, wedging her way into a story where she has no place, baffling test audiences and wearing out set designers. Turn Off the Dark can’t succeed — can’t even be coherent — until Arachne is excised, and Arachne can’t be excised (no matter how many producers and critics suggest it) because Taymor won’t hear of it. This is the predicament at the heart of Song of Spider-Man; this is the spit on which Berger slowly roasts.

The book’s most painful scene comes in the lead-up to the first of what would turn out to be historically many preview performances. Finally, after months of bad press and glitchy rehearsals, the Turn Off the Dark team is going to show the critics what’s what. Look, ye doubters, at these Taymor-designed sets! Listen to these U2 songs! This should be a moment of imminent triumph.

But Berger, watching the show in its last run-throughs — watching Arachne descend bewilderingly from the rafters — has a terrible apprehension.

“For years we knew camp was a threat, and we were going to avoid it. But we stepped in it anyway. And the first preview was in forty-eight hours. It was like waking up to discover you’ve drifted into the wrong lane and now traffic was coming straight at you, and there was no time, no time.”

The aptness of this image makes my palms sweat. The artist can only do what she does by sinking into a state that does, in its innocence and unguardedness, in its weird fecundity, resemble sleep. And this means, inevitably, that the artist will occasionally awaken (when sitting in a preview audience, when rereading an already-submitted draft) to the terrifying sight of headlights. The shock, the shame, the panic — it really does feel existential, even if all that’s at stake is the esteem of strangers. Song of Spider-Man seems, at first, to be a story about a particular bloated musical, but it turns out to be a story about the script in your Outbox, the novel in your documents folder. It’s laughable and excruciating. It’s absurd.