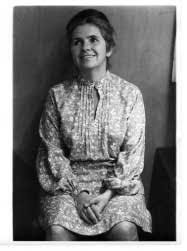

Grace Paley, "A Conversation with My Father"

bothering the grownups & planet-wide embraces

“She had a son whom she loved because she’d known him since birth (in helpless chubby infancy, and in the wrestling, hugging ages, seven to ten, as well as earlier and later.)”

The fiction writer, like a toddler, tugs at the sleeve of the reader (who is busy cooking dinner, or paying bills, or who is just enjoying being left alone for the very first time all day) and says, Wanna play pretend?

And sometimes, sometimes, the reader says yes. And then it is up to the writer — using her full bag of childish tricks: funny voices, sudden changes of scenery, unexpected explosions — to keep the reader engaged, to prevent him from drifting back to whatever adult business he was engaged with, to make him feel (this only happens rarely) that life in this pretend world is somehow more vivid and interesting than life in the the actual world.

You could spend a lifetime learning to do this (I’m well on my way) and still get hardly anywhere with it. But you do learn fairly quickly what not to do, what types of story-developments cause your reader to develop a sudden interest in his email. The list is long (nonsensical character decisions, narrative incoherence) but somewhere near the top has got to be: proposing a second game of pretend right in the middle of the one you were already playing.

And yet writers do this all the time. As soon as I realized that Jean Hanff Korelitz was, in The Plot, going to subject us to chapters of the novel that a character was writing, I was out. The moment I understood that Anthony Horwitz’s Magpie Murders was going to feature hundreds of pages of the book that an editor-character was reading, I had a new book for the giveaway bin. Writers who can make a fiction within a fiction work — who can get us to happily dig into our pockets for a second token of disbelief-suspension — are rarer than writers who can write creditably in multiple languages.

So Grace Paley’s “A Conversation with My Father” deserves to have its jersey hung in the literary rafters. It is not only a great short story full of Paley’s characteristic wit and compassion and linguistic vigor; it’s two.

The story begins with the narrator’s father (“eighty-six years old and in bed”), complaining that the narrator’s short stories have grown too complicated.

“I would like you to write a simple story just once more,” he says, “the kind de Maupassant wrote, or Chekhov, the kind you used to write. Just recognizable people and then write down what happened to them next.”

And so the story consists of the narrator (let’s call her, I don’t know, Paley) trying, for her father’s sake, to serve up a plate of literary meat and potatoes.

Finally I thought of a story that had been happening for a couple of years right across the street.

A neighbor of Paley’s, she tells her father, had a son who became a junkie. And then that neighbor — in a reckless bid for closeness with her son — herself became a junkie. And she remains one, even though her son has now sobered up. The end.

The father isn’t satisfied.

“You misunderstood me on purpose. You know there’s a lot more to it… You left everything out. Turgenev wouldn’t do that.”

And so Paley takes another crack at it. “‘But it’s not,’” she warns her father (and us), “‘a five-minute job.’” And sure enough — the margin grows; the font shrinks. We’re in for it: a true story within a story.

Once, across the street from us, there was a fine handsome woman, our neighbor. She had a son whom she loved because she’d known him since birth (in helpless chubby infancy, and in the wrestling, hugging ages, seven to ten, as well as earlier and later.)

This is the crucial moment — Paley is asking us to disassemble the set (the bed, the pillow, the father, the writer) she asked us to build three minutes ago and to erect, in its place, an entirely new production: an apartment, a “fine handsome woman,” a beloved son. Who could be bothered?

Well, I could, despite my passion for flinging aside stories-within-stories. And it’s entirely because of that second sentence. Even more specifically — it’s because of that parentheses.

(in helpless chubby infancy, and in the wrestling, hugging ages, seven to ten, as well as earlier and later.)

Here is a parentheses like a candy bar rich with caramel and nuts. Helpless chubby infancy is itself an expression of helpless adoration — she could have left it out, but the intensity of maternal adoration demands elaboration. And the wrestling, hugging ages, seven to ten — here she slaps a formal designation, like the Bronze Age, onto a period of life we might never have considered in isolation; we happily stroke our family-historian chins. And then the best and strangest and most deliciously Paley-esque part: as well as earlier and later.

This has the panicky, faux-formal tone of a woman acting (ill-advisedly) as her own counsel: I was at home at seven o’clock, your honor, as well as earlier and later. But this is the authentic, desperate sound of parental love. The mother set out — through Paley’s third-person account — to list the phases in which she had known her son, and she realized, at the last sweaty instant, that no list could possibly capture it. She was there for the unsummarizable all of it — that earlier and later are like two arms flung hopelessly around the equator of a planet.

And so we are invested in this inner-story for the same reason we were invested in the outer-story: because it emerged from the burbling, busy, painfully clear fountain of Grace Paley’s mind. Instead of feeling that we have suspended our disbelief twice, we feel that we have suspended it zero times. We believed in Paley and her father and we believe in the neighbor and her son. Paley learned the great lesson of all those who would deign to bother the grown-ups: you tell them you have something important to show them; you don’t tell them you’re pretending at all.

Totally agree with the irritation over story within a story device. I even drop a book that includes too many correspondences! The play within a play only works for Shakespeare!!

It's the urgency of Paley that ropes me in