Lesley McLennan and Julie Peck, Moving from the Inside Out

napkin-wrapped spoons & decades-old misapprehensions

“Anyone who has broken a bone knows it is painful, but the bone itself is not sending the pain message; it is changes in the tissues around the bone that excite the sensors of the nervous system.”

The writer packs a lunchbox for the reader (crisp strips of dialog, plot sandwiches, little linguistic treat-packets) and periodically the reader looks up with an exasperated expression and says, Hey, thanks for the applesauce — but what exactly am I supposed to eat it with?? The reader has found some little gap in the writer’s planning or thinking, some failure of attention, and he feels the indignation and slight fear that come with being poorly taken care of.

And the best thing, for reader and writer both, is when the writer can at this moment clear her throat and give a significant glance toward the napkin-wrapped parcel one inch from the reader’s hand. The reader, feeling sheepish and gratified both, discovers that the writer remembered to pack a spoon after all and so his indignation was misplaced. And from that point on he will riffle through each day’s lunch with less suspicion and more pleasure.

My most recent passage through this petty-irritation-to-humble-appreciation cycle came partway through Lesley McLennan and Julie’s Peck’s Moving from the Inside Out. Their book is about Feldenkrais (a type of physical therapy about which more later) and in the passage in question they are talking about bones.

Gravity creates the need for bones, and muscles are needed to move the bones.

One sentence in, I’m excited. I adore writing that reduces things to Sesame Street simplicity, that treats the reader to a fresh and fundamental explanation of some piece of equipment (a body, a sense of the physical world) that he has lived with dully for decades. Why do we have bones? is the type of question that only a child would ask — and usually the parent would be too exhausted (and, he’d quickly realize, too ignorant) to answer.

McLennan and Peck go on:

Tellingly, our nervous system is not that interested in our bones. We can’t sense the bones in the same way we sense our skin is cold, or a muscle is working.

Here is where my throat begins to tighten with the sense that someone has forgotten to pack me a spoon. Our nervous system not interested in bones?! Tell that to someone with a broken leg!

However, the nervous system is extremely interested in where the bones are in relation to each other, and in relation to surrounding tissue.

And my certainty that they have failed me deepens. Here I was all excited about this book and they couldn’t even be bothered to —

Anyone who has broken a bone knows it is painful, but the bone itself is not sending the pain message; it is changes in the tissues around the bone that excite the sensors of the nervous system.

Oh.

So not merely was I wrong that the authors had failed to consider the matter of broken bones — I was wrong about how broken bones worked entirely! They not only packed me a spoon; they packed me a variety of applesauce that I had never heard of and will now recommend to everyone I meet as if I invented it.

But allow me to pause here to explain a bit about Feldenkrais. (And I warn you that I have rarely been so enthusiastic about something that I understand so little — a perilous combination.)

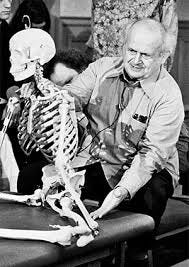

In the early 1940’s a Ukrainian man named Moshe Feldenkrais slipped on the deck of a submarine and aggravated an old soccer injury in his knee. The war made it impossible for him to have surgery, so instead (he was an engineer by training) he set about exploring the mechanics of his injury himself. If he moved this way did it feel better or worse? What about if he made his non-injured leg move like his injured one?

Soon he was walking again — and the word got out about this gruff little rehabilitative genius. He broadened his exploration, so that it encompassed every remote corner of our anatomy, and he organized his findings into a system of simple and non-strenuous exercises. You do one, thinking all the while that this couldn’t possibly be achieving anything, and then you discover that for the first time in living memory you can touch your toes.

Feldenkrais was, I truly believe, a prodigy in his understanding of human movement. He was, however, a terrible writer, and so the half-dozen-or-so books he left behind are less likely to rehabilitate you than to sedate you.

Which is where McLennan and Peck’s Moving from the Inside Out comes in. Their book, helpfully and playfully illustrated, conversational in tone and transparently clear, is everything that you wish Feldenkrais’s books were. They demonstrate again and again the profound and encouraging truth that we knew how to move once (watch a toddler squat to check out the contents of a low shelf) and that we can move like that again. I learned from it, among other things, that for a mere forty-two years I had been mistaken about what my hips were (hint: they are not the things with which you might administer a hip-check).

The great revelation of Feldenkrais — the thing that distinguishes it from the many other systems of bodily self-improvement — is that it presumes you will forget everything: it doesn’t expect you to be walking down the street, reminding yourself with each step to flex this and hoist that. You will, instead, be relying on the far greater intelligence that resides in the depths of your nervous system, the intelligence that knows how to swallow a mouthful of water (but could never explain it). This is the intelligence that the exercises, which can seem so puzzling and pointless to our daily selves, are really speaking to. This is the intelligence that continues to take care of us when we, bereft in the lunchroom, are most certain that we’ve been forgotten.

And now, I've learned something new and added another book to my "must read" list. Luckily, I've never broken a bone but, at 72 years old, I need to learn more about how my knees and hips work.

I'm going to start asking myself "Did you pack a spoon?" for everything I write from now on. Bravo. Also I'm reading Dayswork now and am grateful for the recommendation! I love how the wife paints the most beautiful portrait of her husband in roughly half a page by listing all of the places she couldn't find him.