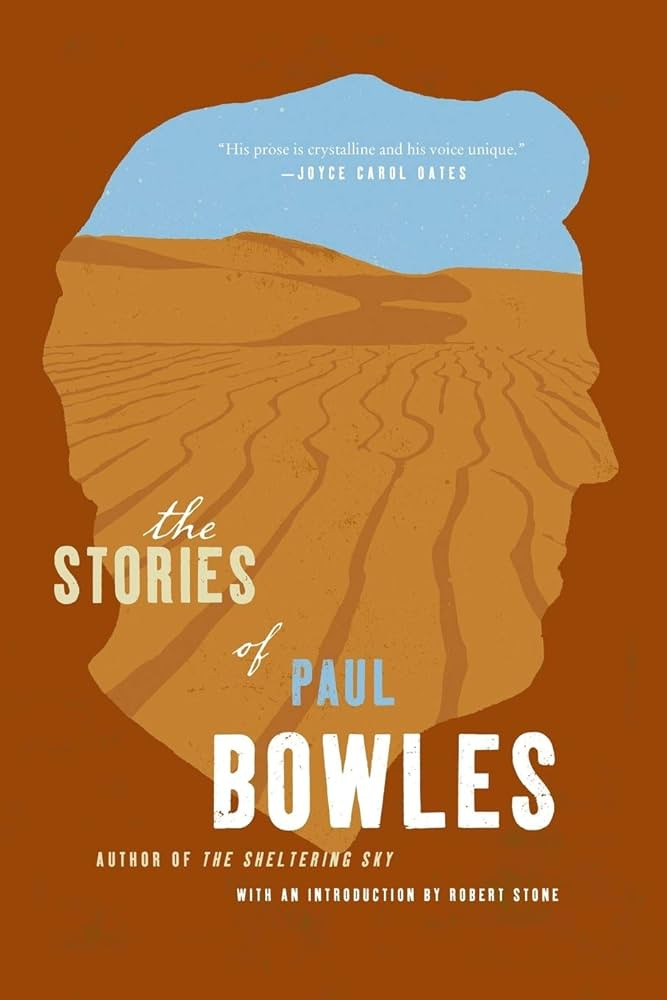

Paul Bowles, "A Distant Episode"

camel udders & pilot lights

“Someone dealt him a terrific blow on the head, and he thought: ‘Now at least I shall lose consciousness, thank Heaven.’”

Some stories you dream before you read them. These stories (I’d put about half of Kafka’s stories in this category, along with bits of Arthur C. Clarke) are made from such resonant, intimate, primal stuff that your skin prickles throughout with the eerie realization: I’ve been here before. And I really have dreamt, many times, of walking down a poorly lit path toward a frightening outdoor gathering, just like the protagonist of Paul Bowles’s “A Distant Episode.” But my dreams have always had the good sense to cut off before I reach my destination. Bowles does us no such favor.

“A Distant Episode” (the best of Bowles’s many literary excursions to Morocco, where he lived for fifty years) is about the hellish vacation of a man we know only as the Professor. He drifts into town (“…air which began to smell of… orange blossoms, pepper, sun-baked excrement…”) hoping to see a cafe keeper he befriended on a trip ten years earlier. He quickly learns that the cafe keeper is dead. This counts, on the scale of disappointments to come, as a stubbed toe.

He decides that he’ll salvage the trip by getting as a souvenir some of “those little boxes made from camel udders” (you know the ones). An unaccountably hostile local offers to take him to the place where the boxes come from, but warns that this may bring them into contact with the Reguibat (an actual Berber tribe who, in the story, play a role something like the Taliban). No matter, thinks the Professor. He really likes those boxes!

The bulk of the story consists of the Professor discovering just how catastrophically he has miscalculated. He’s beaten, kidnapped, and eventually subjected to such degradations that you will read the story’s last pages with the expression of a person watching a loved one’s major surgery. Bowles is faultlessly decorous throughout (“He could not distinguish the pain of the brutal yanking from that of the sharp knife”) but the agony comes across. Rarely has having nerve endings and consciousness been made to seem like such misfortune.

But what makes the story great — what makes it much more than just a high-toned installment of Saw — is our sense, throughout, that all this brutality means something. The Professor’s motivations, from the beginning, are dream-like in their stubbornness and opacity. (Just how good a friend was this cafe owner? Did the Professor not want to confirm before visiting that his friend was in town or, you know, alive?) But dream-like too is the Professor’s suffering. With its weirdness and its specificity — he’s strung with bits of metal like a human tambourine; he’s forced to dance for his laughing captors — it stirs some chilly depths of recognition in us. Are we the Professor? Are we the Reguibat? The story’s disconcerting answer (and the reason you’ll find yourself pushing this story on people, like some urgent but unfathomable warning with which you’ve been entrusted) is: both.

Because early in the evening of his kidnapping, before things have gotten quite so surreally dark, the Professor finds himself being pummeled by a group of men. Bowles writes:

Someone dealt him a terrific blow on the head, and he thought: “Now at least I shall lose consciousness, thank Heaven.”

This sentence is, for me, the key to the story. The writing is courtly (the antique use of terrific; that Thank Heaven like a doffed cap from a man sinking to his knees). But the meaning is hair-raising. Because the sentence ushers us into the Professor’s innermost backstage room — the private little perch of awareness from which each of us watches even the most dreadful or wonderful moments in our life. The part of you that thinks, even as tears stream down your face at your wedding, Wow, I guess I can cry from happiness. The part of you that thinks, at your parent’s deathbed, Well, this is really it, what a momentous scene. Even as the Professor is beaten by strangers and attacked by dogs, some calm and reasonable thing within him is watching it all unfold and working out the collateral gains of passing out. The pilot light of consciousness never extinguishes.

And that sanctum of the Professor’s, that essential humanness, is precisely the thing that the Reguibat refuse to believe in. Or choose not to believe in. He becomes “a possession” to them — thus can they cheerfully throw him in a bag and fail for days to feed him. This is the terror that the story is about — the terror of falling into the hands of people for whom you are less than a person.

And the brilliance of the story is how deeply it implicates us in this tendency to dehumanize, even as it makes us feel the full horror of it. On the first page, the Professor casually notices the “usual swarm of urchins… screaming beside the bus” (swarm!). How real are their inner sanctums to him in that moment? You could even, pushing things a bit, think of the camels, moaning in unspeakable agony while their organs are harvested to make the tchotchkes that the Professor will forget at the bottom of his suitcase.

The overwhelming and unbearable fact is that if you could somehow keep in mind the simple sentience of absolutely everyone, there would be no distant episodes. Everything, whether in the farthest hinterlands or the nearest cities, would happen right where you live.

I remember well being haunted by this story by Bowles in Halpern's anthology The Art of the Tale, long ago, thinking something along the lines of what the desert does to the constructed intellect - picking the bones clean - is built on its disregard for language as the arbiter of reality.

Thanks for this. As always, beautifully and concisely written.

Great piece. I loved reading this. Thanks much