“I eyed it sourly.”

When winter has gotten lost on its way to the exit; when the news is a buffet of acid-dipped razor blades; when you and everyone you know seems to be sick with something dire — P.G. Wodehouse.

A few pages into any one of his books, I feel a kind of sedated, sinking-low-in-a-bathtub happiness spreading through me. The Drones Club, the misdirected marriage proposals, the furious telegrams from aunts. There my Jeeves Omnibus, waiting on the shelf like a dog by the fireplace, ready in an instant to burst into lively debate over which jacket to wear to dinner and which train to take out to the country estate where an intricate but low-stakes fiasco is unfolding. Reliable pleasures, delivered with reliable buoyancy (if you become a Wodehouse-addict you will at some point (a) be reading one of his books and wonder if you’ve read it before, and (b) realize quickly that you don’t care).

Ordinarily when I laugh while reading at night my wife will ask me what’s so funny and I, once I’ve gotten hold of myself, will tell her. But with Wodehouse it’s hopeless, because my chortling is incessant, like the burble of an appliance in self-cleaning mode. This steady contentment must, it occurred to me recently, be why twenty-somethings rewatch Friends. But Friends doesn’t come encased in some of the deftest, most meringue-light prose of the 20th century.

Flipping pages almost at random:

… I had seen quite a bit of her. Indeed, in my moodier moments it sometimes seemed to me that I could not move a step without stubbing my toe on the woman.

…

There is something about him that seems to soothe and hypnotize. To the best of my knowledge, he has never encountered a charging rhinoceros, but should this contingency occur, I have no doubt that the animal, meeting his eye, would check itself in mid-strike, roll over and lie purring with its legs in the air.

You know that dismaying moment when you’re listening to someone at a party and, while attending grimly to his explanation of how his firm specializes in this sort of merger but has lately been venturing into this other sort of merger, you realize that his eyes have gone dead? That he is not only boring you but boring himself?

This is precisely what Wodehouse never does. He is at every moment alert to the reader’s experience, aware of precisely how long it’s been since he last granted us a chapter break, tucking a one-bite joke into a line of dialog, threading a wonderfully deranged simile through a bit of stage-business. He can write Jeeves (the omni-competent butler who is to Wodehouse’s oeuvre what Sherlock Holmes is to Conan Doyle’s) because, for the reader, he is Jeeves, forever at the ready with precisely the concoction that his comparatively dim client does not yet know he needs.

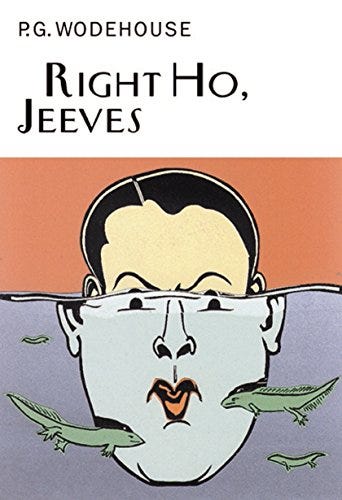

Watch him at work in Right Ho, Jeeves (as good a place to start as any). Late in the book, for reasons that are both too complicated and too delightful to explain, Bertie — the mishap-magnetizing toff who narrates the books — is about to set off on a middle-of-the-night bike ride. Jeeves (who manages Bertie more or less as a parent manages a toddler) has contrived this errand. Bertie speaks first.

“Where is this foul bone-shaker?”

“I will bring it out, sir.”

He did so. I eyed it sourly.

Notice first how easy the dialog is to follow, despite its lack of attribution. Bertie speaks in long and sloppy swings, imagery and abuse flying from him like beads of sweat. Jeeves replies in badminton volleys.

But my favorite bit — and my favorite sentence in the book — comes after the dialog. I eyed it sourly. Here, perfectly within the key of Bertie’s temperament and diction, is a miniature linguistic contraption for the reader to play with before he races off through the night.

What fun it is to say! I eyed, with its consecutive long i sounds, has some of the mouth-clacking pleasure of I-edited-it, but without quite that progress-halting level of oddity. And then, after that stutter-stepping start, Wodehouse launches us smoothly out onto the ice with that long-e glide of sourly.

I-i-ee. I-i-ee. Bertie is sour, but we, climbing aboard his bone-shaker, are beaming like infants discovering the pleasurable, tongue-testing shapeliness of sound. Wodehouse could have written — most writers would have been perfectly content with — I regarded it warily, but he, writing at a time when his was the continent falling apart, wanted us to have this half-second of bliss. Humans are (look around) vindictive and nasty and disappointing in too many ways to count. But they’re like this, too.

Love this, and of course love Bertie Wooster.

Thanks for reminding to dip once more into the Omnibus, conveniently placed nearly at the end in my bookshelf, ahead of Zola. My sister joined a book-buying club in her first year of secondary school, over 60 years ago and the very first book she brought home was a penguine paperback edition of a Jeeves book. It must have been one of the first adult books I read (I was still in primary school). Oh, what bliss.