“Hamilton left the door open, and then he thought better of it, and closed it halfway.”

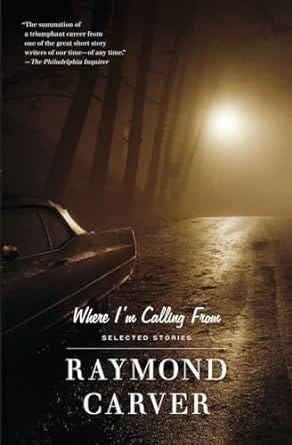

Raymond Carver had a literary allergy to tricks of any kind. Which, like an allergy to gluten, sounds simple enough — an admirable bit of self-care, really — until you get down to examining ingredient lists.

Twist endings, those are probably tricks. Dialogue cleverer than any non-Oscar-Wilde human could ever manage in actual conversation: a trick. But is having the speed of your prose accelerate and decelerate according to the action you’re describing — pacing, in other words — a trick? Is humor a trick? Are contractions a trick?

Some minimalist writers are so insistently non-tricky — so flat and spare and surveillance-video-like — that their non-trickiness can become a trick in its own right: think of Knausgaard in his impeccable leather jacket glowering at you for 3,600 pages. But Carver wouldn’t even allow himself this modest indulgence. His gluten-free muffin sits on a paper plate, under bleak fluorescent tube-lights, defiantly un-buttered.

Which is why I’m always surprised to discover, when I reread Carver, how delicious his stories are, how nourishing. When you make the absence of trickery a cornerstone of your writing — when you make it a religious practice, almost — the Gods occasionally reward you with a flash of the thing that the tricks can only feebly imitate: magic.

The clearest instance of Carverian magic I know happens at the end of “Bicycles, Muscles, Cigarettes.” The story begins with a man, Hamilton, getting summoned to a neighbor’s house because his pre-adolescent son has gotten into some trouble regarding a bike. The trouble, as explained by a neighborhood boy, is vague:

“I don’t know for sure. I don’t understand all of it. He and Kip and this Gary Berman are supposed to have used my brother’s bike while we were on vacation, and I guess they wrecked it. On purpose. But I don’t know.”

Carver is known for being good at depicting a certain cluster of adult difficulties — alcoholism, marital unhappiness, lost jobs. But he’s just as good on the inscrutable, writhing quality that children’s problems have when they’re flipped over and subjected to official attention. Whatever Hamilton’s son, Roger, has gotten up to with this bike, Hamilton is, we have the sense, going to sigh deeply before he gets back home.

Most of the story’s twelve pages take place inside the neighbor’s kitchen. A group of kids and their bewildered, prickly parents conduct a kind of unofficial trial, in which no one is quite sure who is a juror and who is a defendant. There are more names and characters than we can keep track of — Kip, Gilbert, a boy sitting on the draining board, a boy on the telephone, the mother of the boy whose bike was wrecked. Gary choked Roger, or maybe Roger started it. We, like Hamilton, have been dragged from whatever we were doing into the middle of some stranger’s incomprehensible mess. One of the few things we know with certainty is that Gary Berman’s father will be here shortly.

“Did you get one of Kip’s parents?” the woman said to the boy.

“His sister said they were shopping. I went to Gary Berman’s and his father will be here in a few minutes. I left the address.”

This promised arrival is shark music. And after another page or two of squabbling, the shark appears.

A stiff-shouldered man with a crew haircut and sharp grey eyes entered the kitchen without speaking.

The parents to this point have been civil, but Gary Berman’s father is something different — he stands behind his son’s chair, barking accusations like some mix of a bodyguard and a prosecutor. Gary and his father storm out; Hamilton and Roger leave shortly after. And then the action of the story takes place: Hamilton and Gary Berman’s father get into a fistfight in the front yard.

Berman brushed Hamilton’s shoulder and Hamilton stepped off the porch into some prickly crackling bushes. He couldn’t believe it was happening. He moved out of the bushes and lunged at the man where he stood on the porch.

After a few frenzied minutes the men, breathing heavily, separate. The women stare, horrified; the boys, exhilarated, start play-boxing. Hamilton and Roger slink home. And before going inside, Hamilton takes a minute to gather himself on the porch.

He had once seen his father — a pale, slow-talking man with slumped shoulders — in something like this. It was a bad one, and both men had been hurt… Hamilton had loved his father and could recall many things about him. But now he recalled his father’s one fistfight as if it were all there was to the man.

I never quite know what people are talking about when they use the word theme, but with this passage, the story feels to me thematically full. We have generations of sons watching generations of fathers getting in fights. We have Hamilton reckoning with his own eventual reduction to a single queasy memory. We have unspoken regret and possibly-even-more-unspoken pride.

Carver could end the story here (He was still sitting on the porch when his wife came out.) and we would close the book with that Gordon-Lish-trademarked feeling of pregnant truncation. Minimalist masterpiece achieved.

But Carver has Hamilton go upstairs to say goodnight to Roger.

“It’s pretty late, and you’re still up, so I’ll say goodnight,” Hamilton said.

“Good night,” the boy said, hands behind his neck, elbows jutting.

Hamilton can’t quite seem to land the plane, goodnight-wise. He gives Roger some half-hearted warnings about staying away from that group of boys, then tries again.

“Okay, then,” Hamilton said. “I’ll say goodnight.”

(Is this him saying goodnight? Or is there some future word or gesture that will constitute the actual goodnight? The koan comedy of this moment is very Carver.)

In any event, Roger has more to say before he’ll let his father out of the room, and he seems to have a child’s disconcerting ear for telepathic signals.

“Dad, was Grandfather strong like you? When he was your age, I mean… When you were young, was it like it is with you and me? Did you love him more than me? Or just the same?”

Hamilton parries his way through this barrage as well as any tired and aching parent could. But then Roger catches him with a body shot.

“Dad? You’ll think I’m pretty crazy, but I wish I’d known you when you were little. I mean, about as old as I am right now. I don’t know how to say it, but I’m lonesome about it. It’s like — it’s like I miss you already if I think about it now. That’s pretty crazy, isn’t it? Anyway, please leave the door open.”

Anyway, please leave the door open! Never has the freakish and fickle clairvoyance of children — their habit of condensing uncanny insights into single phrases, and then immediately asking if they can have extra bags of Pirate’s Booty — been so well-depicted.

But the line about the door is also a straightforward, literal request. And Carver is, of course, nothing if not straightforward.

Hamilton left the door open, and then he thought better of it, and closed it halfway.

Now the story is done. And now we see what Carver gets for all those pages of scrupulously denied tricks. Because this ending would, in a court of law, hold up as straight reportage: a boy said something weird and sweet, then asked for the door to be left open, and the father, after a moment of thought, complied. Carver’s trick-free certification is still intact.

But because we are by this point feeling so much — because we have been convinced, by everything that came before, that what we are dealing with here is not literary reality but actual linoleum and prickle-bush reality — we are positively brimming with a sense of meaning. And it isn’t cheap, English-paper-ready meaning (The doorway represents Hamilton’s untamed nature, and by leaving it halfway open…); it’s the kind of meaning we feel when we go to take the trash out and notice the full moon hanging above the roof. It’s the kind of meaning we feel when we come across photographs of our parents as children. It’s a hell of a trick.

Long ago, someone told me that Carver kept a note taped above his desk that read, "No Cheap Tricks!" You've done a wonderful job showing what this means and how it was a near religious practice for Carver, and the magic that resulted. Well done!

I've read some Carver stories and resisted reading more. That changed after this piece. One of your most compelling -- and that's saying something. Thanks again.