“Would you think he was anybody like you?”

Great novels don’t need great last sentences. Lop off the last line of Moby Dick or War and Peace and hardly anyone would notice (War and Peace would, in fact, benefit from having its last ten-thousand lines cut).

Short stories, though, are less forgiving. Cut the last line of “The Dead,” with its faintly falling falling faintly snow, and its claim on greatness would evaporate overnight. Airliners need merely to deliver you to the proper region (welcome to the city of Catharsis/Resolution/ Disquiet; enjoy your stay). Gymnasts need to stick their landings.

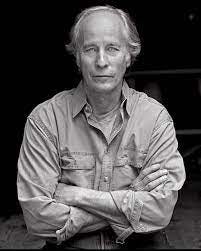

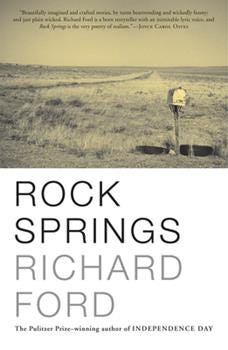

The most gloriously stuck landing in modern American literature (arms triumphantly out-flung, leotard microscopically heaving) comes from Richard Ford’s “Rock Springs.” It consists of neither a plot twist nor a linguistic swell; it’s a sentence so seemingly plain it could be printed on a cheaply Xeroxed flier flapping from a utility pole. The flier just happens to feature a photo of your own staring and stricken face.

“Rock Spring” starts out — and remains, for nearly the entirety of its twenty-six pages — a quietly heartbreaking improvisation in the key of Raymond Carver. The narrator, Earl, is a small-time thief with a discontent girlfriend, a young daughter, and an imperishable run of bad luck.

“Edna and I had started down from Kalispell, heading for Tampa-St. Pete where I still had some friends from the old glory days who wouldn’t turn me in to the police.”

Earl has, it turns out, been writing bad checks. And so he and his makeshift family are fleeing Montana for the promise and laxity of Florida.

“But we were half down through Wyoming, going toward I-80 and feeling good about things, when the oil light flashed on in the car I’d stolen, a sign I knew to be a bad one.”

And so they drift to a stop in a mining town called Rock Springs, where the indignities of being poor and on the lam (has someone reported the car stolen? whose phone can they use? what will they eat?) surround them like a poison gas.

They meet a few locals — each one quickly, memorably drawn — and exhaust each other’s patience and arrive, on the last page, at the moment when Earl needs to steal another car. And this is where the story leaps out of the realm of booze-and-misdemeanors-realism (Denis Johnson drinking down the bar from Charles Bukowski) and lands squarely in the ranks of greatness.

Earl is up in the middle of the night, prowling the Ramada parking lot, peering through windshields. He finds a promising Pontiac, with maps and sunglasses and a cat-carrier inside.

“It all looked familiar to me, the very same things I would have in my car if I had a car. Nothing seemed surprising, nothing different. Though I had a funny sensation at that moment and turned and looked up at the windows along the back of the motel.”

Without so much as a paragraph break, the angle begins to shift:

“All [the windows] were dark except two. Mine and another one. And I wondered, because it seemed funny, what would you think a man was doing if you saw him in the middle of the night looking in the windows of cars in the parking lot of the Ramada Inn? Would you think he was trying to get his head cleared? Would you think he was trying to get ready for a day when trouble would come down on him? Would you think his girlfriend was leaving him? Would you think he had a daughter?”

After twenty-some pages inside Earl’s troubled head, Ford invites us, in this last paragraph, to look at Earl as if in surveillance footage. What would you think a man was doing? Like jurors confronting one last bit of evidence at the end of a long and depressing trial, we stare at the distant, misbehaving figure and shake our heads in pity and sorrow.

But Ford has one line left.

“Would you think he was anybody like you?”

Your heart stops when you read this line — or mine does anyway. The subtle corporeality of that anybody, rather than anyone. The desolate quiet of that final question mark. The man in the surveillance footage just looked into the camera and met your eyes. And his were not, unfortunately, the eyes of a stranger.

Exactly how many layers of unhappy chance stand between you and Earl? How many credit cards would need to fail before you’d find yourself in that parking lot? How many relationships? It turns out that you’ve had your position in this hastily assembled courtroom all wrong. You aren’t a juror at all. You’re the accused.

Thanks for reminding me of this story! I remember reading it in Carver’s American Short Story Masterpieces. The ending still knocks me out. Oddly, I was just listening to Malcolm Gladwell’s short discussion on narrative endings this morning. https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/revisionist-history/a-treat-for-the-die-hards

Really enjoyed this! The story turns into a scary mirror! Thanks