“‘Me?’”

A piece of dialogue gets written (“Help! He fell this morning,” said Helen. “Could you come over?”) and then, like a freshly minted car door, it sets off down the assembly line for improvements. The first station cares merely about naturalism: is this actually how people talk? (Maybe it should have a bit of the choppiness of panic in it? “He fell! On the stairs. Where are you?”) Distinguished employees at this station include Henry Green and George V. Higgins.

The second station concerns itself with function: does this line, with its fresh coat of verisimilitude, still convey the necessary information? (The reader needs to know that he fell in the morning. Could it be “He fell down the stairs! He was just coming down to breakfast and — Where are you?”). Haruki Murakami is especially good at this sort of thing. So is Penelope Fitzgerald.

And that’s all the treatment that most dialogue gets: sanded and authenticated, off it goes to join its car body of polished description and crumple-proof plot.

But there’s a little-known third station in the dialogue factory — rarely visited, highly specialized. This station concerns a subtler and stranger question: does this dialogue capture the surreality of human conversation? I refer here not to the strangeness of individual bits of phrasing; that’s all covered back at station one. I’m talking about the Dadaesque shape of conversation, how the plumber can describe what needs to be done in order to get your sink working again and then, having told you, tell you twice more, as if stuck in a traffic circle. Or the way that you can find yourself asking, at the end of a ten minute discussion of spring break plans, if the person you’re speaking to has any plans for spring break. The almost-unbelievable repetitiousness, the Rube Goldberg inefficiency, the cul de sacs and stretches of meaninglessness and autopilot collisions. Does this piece of dialogue capture that?

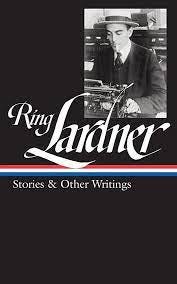

This station has had the same employee of the month for so long that his picture (hat rakishly askew) hangs inside a locked and gilded frame. I refer, of course, to Ring Lardner.

Lardner is a comic writer from the 1920’s — a socially peripheral but artistically integral member of Dorothy Parker’s Algonquin set— and the best place to see his singular gift for dialogue is in an essay called, appropriately, “On Conversation.”

“The other night I had to be coming back from Wilmington, Del. to wherever I was going and was sitting in the smoking compartment or whatever they now call the wash room and overheard a conversation between two fellows who we will call Mr Butler and Mr Hawkes.”

And that’s all the piece is — two pages of eavesdropping on the conversation of two unremarkable men on a train. No plans are hatched, no secrets are revealed. In fact Mr Butler and Mr Hawkes (who it turns out came from the same town and haven’t seen each other for years) are notable only for the uncanny banality of their talk.

“‘Where are you headed for?’ asked Hawkes.

‘Well, I am going to the big town,’ said Butler.

‘So am I, and I am certainly glad we happened to be in the same car.’

‘I am glad too, but it is funny we happened to be in the same car.’”

Already you can feel, in the disdainful Dick and Jane stiffness of the diction, Lardner setting aside the goal of verbatim accuracy; he’s after bigger game.

‘How long since you been back in Lansing?’

‘Me?’ replied Butler. ‘I ain’t been back there for twelve years.’

‘I ain’t been back there either myself for ten years. How long since you been back there?’

‘I ain’t been back there for twelve years.’

‘I ain’t been back there myself for ten years. Where are you heading for?’

On and on they go like this (they exchange the information about how often they get back to Lansing six times, by my count), an accidental Laurel and Hardy routine on the Metro North. I love the boldness of what Lardner’s up to here — his determination to capture the almost-literally-unbelievable vapidity of most of what comes out of our mouths — but what I love even more is that Me?

Butler and Hawkes each say Me? a few times throughout the piece — always as a gulp of air before plunging back into the depthless depths of their conversation — and the first thing I love about it is the acuity of the hearing. That Me? is the adult equivalent of the What? that some kids reflexively dispense in response to a question at school; a demand for a break from the relentless volley of public talk.

But more than that I admire the psychological acuity — how that Me? is not just an instance of senseless conversation but an explanation for it; it’s a squeak of panic reaching the commuters’ dully bubbling surface. Because it’s the terrifying need to assemble an entire self for inspection (this is what I’ve made of myself, this is how often I get home, this is what my life consists of), renewed every few seconds throughout a conversation, that leads us to reach for the comforting detritus of whatever we happened to be saying one minute earlier, the balsa wood of the commonplace.

Me? What a trite verbal filler of a question! And what an existential abyss it conceals! Butler and Hawkes, glad (or “glad”) to have run into each other, are businessmen exchanging pleasantries on a train. And they are drowning.

I've only recently been introduced to your post. Your enthusiasm and energy are contagious and as I entered unmasked, I've got the bug! Thank you for your insightful, delightful essays.

You Can Call Me Al