“And at the same time, his long bony body rose up out of the bed and his bowl of soup went flying into the face of Grandma Josephine, and in one fantastic leap, this old fellow of ninety-six and a half, who hadn’t been out of bed these last twenty years, jumped onto the floor and started doing a dance of victory in his pajamas.”

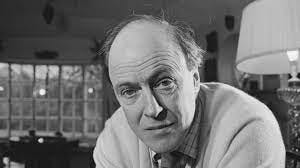

Every few years I read an article whose upshot is: however bad a man you thought Roald Dahl was, he was worse. A bigot, an anti-semite, a dreadful husband and father — he has, since his death in 1990, been making us queasy as dependably as he once delighted us.

The queasiness is real, and important. (Here, for instance, is a pair of sentences that we very much won’t be celebrating: “There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity, maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews. I mean, there’s always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere; even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.”)

But the delight Dahl gave was real too — and worth trying to understand. Dahl was the first writer I remember appreciating as a writer: I wanted to read his books not because their subjects appealed to me or because they were on display at the library but because they were by him. I had known, from other books, that reading could be fun — Louis Sachar or Jerry Spinelli was a solid substitute when I’d exhausted my daily half hour of TV — but I hadn’t known that reading could seal you in a world that felt more spacious and interesting and true than the actual world. It had never occurred to me that reading was an activity I might come to love.

Loving to read is now a cliche, a worn bit of needlepoint meaninglessness, but think how peculiar and precious a thing loving to read actually is. What an extraordinary, silent, inexpensive, improbably restorative refuge it gives a person. My daughter is now at the age when she is fumblingly sounding out words and writing messages that read like ransom notes (DEER DAD I WOT TOOW EET CANDEE). She hasn’t the slightest clue that these larval mental wrigglings will soon metamorphose into an actual, schedule-disrupting passion. But they will. And it will quite likely happen while she’s holding a book by a man who would have been repelled by her very existence.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is Dahl’s best book — or anyway his most joyful. And joy, strangely, turns out to be one of the secret gears that makes Dahl’s greatness go.

Early on — after we’ve been introduced to the desperately poor and enfeebled Bucket family and the alluring and secretive Wonka factory — we learn something amazing: Willy Wonka has decided to let five lucky children inside. Five ordinary candy bars, already in circulation, have, hidden in their unassuming wrappers, golden tickets.

And of course Charlie — after a deliciously drawn-out sequence of hope and disappointment — finds one.

“Charlie burst through the front door, shouting, ‘Mother! Mother! Mother!’

Mrs. Bucket was in the old grandparents’ room, serving them their evening soup.”

Charlie lives, remember, not only with his parents, but with two sets of grandparents, the four of whom share the family’s one bed. The grandparents never leave this bed, not even to eat the boiled potatoes and cabbage soup that, however briefly, distract them from their regular course of shivering and starving. Chocolate — to say nothing of a chocolate factory — occupies a place in the Buckets’ cosmos something like the place Christian heaven occupied for peasants during the Middle Ages, a tantalizingly vivid window onto kinder circumstances.

Charlie’s news stuns the household into stillness.

“For about ten seconds there was absolute silence in the room. Nobody dared to speak or move. It was a magic moment.”

Then Grandpa Joe — the liveliest and sweetest of the grandparents — begins to stir.

“Grandpa Joe leaned forward and a took a close look, his nose almost touching the ticket. The others watched him, waiting for the verdict.”

Grandpa Joe’s eyes go wide, his cheeks turn pink, and then:

“…suddenly, with no warning whatsoever, an explosion seemed to take place inside him. He threw up his arms and yelled ‘Yippeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee!’ And at the same time, his long bony body rose up out of the bed and his bowl of soup went flying into the face of Grandma Josephine, and in one fantastic leap, this old fellow of ninety-six and a half, who hadn’t been out of bed these last twenty years, jumped onto the floor and started doing a dance of victory in his pajamas.”

What a wealth of understanding is condensed into that last sentence!

Dahl remembers — as strangely few children’s writers do — the true significance of adults in the life of a child. They are not only Greek Gods bestriding the child’s world, doling out punishments and rewards according to ever-shifting rules and whims. They are also, just as importantly, the water baths in which the child’s experiences — fragile and mysterious as film — bloom into visibility. A playground injury doesn’t assume its final form until you’ve seen what it does to your parent’s face. And Charlie’s Golden Ticket isn’t quite real until it’s defibrillated Grandpa Joe into midair.

There are smaller master-strokes in every clause. There’s slapstick chaos (his bowl of soup went flying into the face of Grandma Jospehine) but it doesn’t leave a mark (it is, after all, soup). There is, in Grandpa Joe’s sudden nimbleness, the reversibility of the terrifying withering to which everyone a child loves is subject. There’s the fact that Grandpa Joe, or at least the narrator, renders his age as ninety-six and a half. And there’s dancing — dancing in pajamas — as the ultimate expression of ecstasy.

Grownups’ true feelings are often hidden in strings of text messages, or saved for the moments when children are out of the room. Here they’re as legible — and as awesome — as sky-writing.

All bigots should leave behind such wonders.

"writing messages that read like random notes"...perfection.

It seems as though, every few years, the question is asked whether we can separate an artist/creator from his/her creation. Wagner, Dahl, etc.