“Dr B. smiled again in that oddly dreamy way.”

There’s a genre of dream — a notably cheering and invigorating genre — in which you discover a new room in your house. There, just on the other side of the attic hatch, is a full Olympic swimming pool. Right behind your hall closet lies a bustling two-story restaurant.

Stefan Zweig, an Austrian writer from the period just before the second World War, is the master of this dream’s literary equivalent. You tool along in his books, admiring the lively prose, enjoying the tinge of melodrama — and then you come upon a hidden door. A seemingly insignificant character begins to tell what you expect will be a story of at most a paragraph or two; thirty pages later you find yourself immersed in a different book altogether.

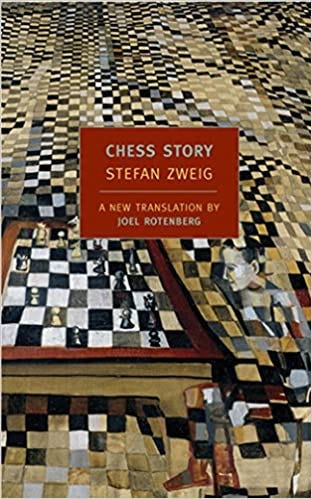

The best showroom for this architectural trick is Chess Story, a novella published after Zweig’s death in 1942. It’s about — or seems at first to be about — the world chess champion, Mirko Czentovic, traveling by boat from America to Argentina. “He’s crisscrossed America from coast to coast playing tournaments and is now off to Argentina for fresh triumphs.”

Even for a chess champion, Czentovic is bizarre. A Yugoslavian orphan, he was still, at fourteen, counting on his fingers, reading with difficulty.

“He did nothing unless specifically told to, never asked a question, did not play with other boys, and undertook no activity that had not been explicitly assigned to him…”

Between chores he sat around “with the vacant look of a sheep at pasture.”

But then he happened upon a game of chess — and found the one narrow sliver of human endeavor in which he was not only capable but brilliant. Off he went, dragged from chess club to cafe, humiliating proud adult amateurs, studying with a minor master in Vienna, bringing glory to his Yugoslavian village. And now, in his twenties, this stolid sheep of a man (“a dull, taciturn peasant lad, from whom even the craftiest newspapermen were never able to coax a single word of any journalistic value”) is the champion of the world.

One of Czentovic’s fellow passengers (who happens also to be the book’s narrator) catches wind of the celebrity on board the ship, and contrives to bait the champ into a game. Each day the narrator readies his chess set in the smoking room — and on the third day, Czentovic finally deigns to wander in.

Soon a small group of chess-enthusiast passengers have assembled to challenge Czentovic — and Czentovic, with all the animation of a cow flicking a fly with its tail, crushes them. But he grants them a rematch, and halfway through the second game, a mysterious stranger wanders by and, seeing the move Team Passenger is about to make, whispers, “‘For God’s sake! Don’t!’” Under this mysterious stranger’s guidance, the passengers (their hearts racing, their pupils widening) play Czentovic to a draw. Let’s have another rematch! Mysterious stranger vs. suddenly-roused champion!

And so here, about thirty pages into an eighty page book, we feel pretty well moved in. The story’s layout seems pleasing, if a tad familiar — here’s the hallway leading to the climactic battle; here’s the balcony of artificially prolonged suspense on which you can enjoy your morning cup of coffee.

But what’s this door over here?

The mysterious stranger (whose name turns out to be Dr. B) runs out of the room. He cannot — he must not — play again. He’s sorry to have interrupted everyone’s game.

The narrator, naturally, pursues Dr. B onto the deck. Why won’t he play? How did he get so good in the first place? Does he realize who he just nearly beat? Who is he?

Dr. B replies cagily, bewilderingly. He has not, he insists, touched a chess piece in more than twenty years. Even if he does consent to play Czentovic again, the passengers must not place too much hope in him. The narrator takes this in.

“I could not help but express my astonishment at the precision with which he had been able to remember every combination of moves played by a variety of chess masters; surely he must have been much involves with chess theory, at least? Dr. B. smiled once again in that oddly dreamy way.”

This passage is the book’s hidden door, and Dr. B’s dreamy look is the intriguing murmur we hear when we press our ear against it.

Because Chess Story, it turns out, is not really Czentovic’s book, and not even the narrator’s. It is Dr. B’s — and we spend the next thirty pages exploring his history, which involves the Gestapo and hidden papers and deranging obsession. We wander through his life with the half-forgetful fascination of a dreamer swimming laps in an unsuspected pool — and then we return to the ship and its chess match feeling fantastically, almost unaccountably, refreshed.

The discovered room in a dream is delightful precisely because of its seeming superfluity. Here we thought we lived already in a complete house; little did we suspect the sprawl of its actual architecture, its secret bounties.

But the feeling that these dreams engender — the suspicion that we possess more than we can ordinarily access or even fathom — is not superfluous at all. It’s vital; it’s sustaining; it’s true. Zweig is its most reliable daytime dispenser.