“He had whirled Danny around to spank him, his big adult fingers digging into the scant meat of the boy’s forearm, meeting around it in a closed fist, and the snap of the breaking bone had not been loud, not loud but it had been very loud, HUGE, but not loud.”

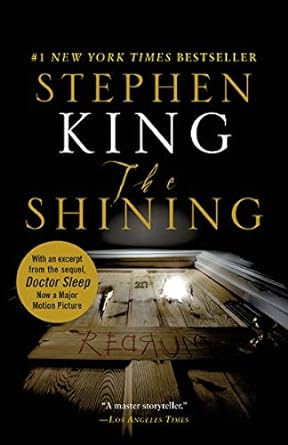

A category of book I often find myself craving is: Stephen King but less so. By which I mean, What if there were a writer as attuned to all that’s weird and unspeakable as King, as singularly interested in story, but who didn’t, say, have such a penchant for frenzied italics? Who didn’t clutter his books up with a high school yearbook’s worth of epigraphs (Springsteen lyrics, Poe stories, nursery rhymes, bumper stickers he once saw …)? Whose books bore the marks of an editor’s pen?

But whenever I find a book that I think fits the bill (Justin Cronin, Chuck Wendig) I invariably find myself losing interest before the halfway point. Some stories — those involving vampires or secret government programs or global plagues from which only a single unlikely child happens to be immune — require a certain deranged energy to carry us past their various improbabilities and embarrassments. There is not, it turns out, a dignified way to spray whipped cream directly into your mouth.

So whenever I feel like reading something Stephen King-esque, I read Stephen King. And the book I go back to most often is The Shining. It’s his tightest and most suspenseful and most psychologically astute book. He doesn’t curb his excesses in it — never — but he puts them to good use.

Early on there’s a scene in which Jack is being shown how to work the Overlook’s furnace. King has a fair amount of table-setting to manage here (“‘The pilot’s got a fail-safe,’ Watson told him. ‘Little sensor in there measures heat.’”) but he wants also, so that we’ll take the trouble of attending to all this dry but important business, to involve us emotionally. So he doesn’t merely give us a tour of the hotel’s inner workings — he simultaneously gives us a tour of Jack’s boiler room too. Specifically: Jack’s most shameful memory, and the proximate cause of their coming to the Overlook — the moment when, in a drunken rage, Jack accidentally broke his toddler son’s arm.

The boiler room scene is speckled with fragments of italics and parentheses, like a news broadcast picking up stray snatches of interference.

Lost your temper.

(Danny, are you alright?)

This is well done, the cool mundanity of the present punctuated by shards of the feverish past — and then, as often happens with King, the fever wins out. He opens a parentheses, describing the moment when Jack came upon Danny standing in his office, and for a good two pages — for so long that we, and possibly King, forget that we’re even in a parentheses — he leaves them open.

Inside this parentheses we get Jack’s discovery of his ransacked drawers, his realization that Danny has poured one of Jack’s beers all over the manuscript of Jack’s play, his reaching out to grab Danny’s arm. And then we get this:

He had whirled Danny around to spank him, his big adult fingers digging into the scant meat of the boy’s forearm, meeting around it in a closed fist, and the snap of the breaking bone had not been loud, not loud but it had been very loud, HUGE, but not loud.

This is the sentence that, if I were in charge, I would engrave on Stephen King’s tombstone. Reading it reminds me of watching Animal from the Muppets play the drums. King is banging on everything in his vicinity — italics, all caps, repetition — to make us feel what he’s feeling. And we do! The tiny, terrible sound of an irreversible mistake. The dumbfounding horror of hurting one’s own child (just scan the sentence as a visual object — the first half, before Jack breaks Danny’s arm, looks like English prose; the second half, once Jack has been poleaxed by what he’s done, looks like it was scratched in the dirt by a very upset Neanderthal).

There are inelegancies aplenty (Martin Amis would have committed seppuku before placing meat and meeting in such proximity) but we are reading too quickly, too absorbedly, to notice. John Updike said, “Nabokov writes prose the only way it should be written: ecstatically.” Well, not all of us are quite so articulate in the throes of ecstasy. Some of us are sweaty and clumsy and we can’t remember if we already told you about that song by Jefferson Airplane and have you ever seen a dead body and did we mention we’re from Maine? We are, in short, too much. But we mean every overspilling word.

😂😂This ends up being ecstatically funny, Ben! I’m planning a rereading of The Shining.

Great argument.

I think what King does best is show us madness in the form of a fractured consciousness.

There are times when it looks like the quote you reference, in which the mind is drifting in and out of the present, rattling around erratically and incoherently.

And there are also times when the mind feels totally disconnected from what it is doing. My personal favorite quote from the book is the part which I consider the climax, in which Jack decides to destroy the snowmobile, their one hope of escape from the Overlook. What he is doing is essentially dooming his family and himself, but his mind is totally calm and nonchalant about the whole thing. Eerie.

Here’s the passage:

~~~

He was standing by the snowmobile’s cockpit, his head starting to ache again. What did it come down to? Go or stay. Very simple. Keep it simple. Shall we go or shall we stay?

If we go, how long will it be before you find the local hole in Sidewinder? a voice inside him asked. The dark place with the lousy color TV that unshaven and unemployed men spend the day watching game shows on? Where the piss in the men’s room smells two thousand years old and there’s always a sodden Camel butt unraveling in the toilet bowl? Where the beer is thirty cents a glass and you cut it with salt and the jukebox is loaded with seventy country oldies?

How long? Oh Christ, he was so afraid it wouldn’t be long at all.

“I can’t win,” he said, very softly. That was it. It was like trying to play solitaire with one of the aces missing from the deck.

Abruptly he leaned over the Ski-Doo’s motor compartment and yanked off the magneto. It came off with sickening ease. He looked at it for a moment, then went to the equipment shed’s back door and opened it.

From here the view of the mountains was unobstructed, picture-postcard beautiful in the twinkling brightness of morning. An unbroken field of snow rose to the first pines about a mile distant. He flung the magneto as far out into the snow as he could. It went much farther than it should have. There was a light puff of snow when it fell. The light breeze carried the snow granules away to fresh resting places. Disperse there, I say. There’s nothing to see. It’s all over. Disperse.

He felt at peace.

~~~

Also, it’s interesting to me that the breaking of the magneto is very similar to the breaking of Danny’s arm