“In her eyes was an expression I would see many times in the years ahead but was seeing that day for the first time, and although I had not the language to name it I had the sentience to feel jarred by it.”

“I think like a genius, I write like a distinguished author, I speak like a child,” said Nabokov. Demonstrating that it’s possible to be simultaneously pompous and self-deprecating — and providing, unintentionally, a useful model for thinking about the work of being a writer.

Picture a three-story office building. The sign above the door reads Literature, Inc. On the first floor are the writers, scrappy and demotic, specializing in speech. On the second floor are the writers (pardon me, authors) with beautiful prose styles. And on the third are the eccentrics (lots of silent pacing and fingernail-chewing) whose main business is the pinning down — the translating into linear language — of thought; these third floor denizens are in the business of sketching smoke.

This is, of course, a rough model. Even the hardiest ground floorists (Elmore Leonard, Henry Green) need occasionally to pop upstairs for a bit of polish; even the most airily cerebral (Proust, Woolf) need regular invigorating splashes of speech. But writers do tend to return to their desks. We know where to find them.

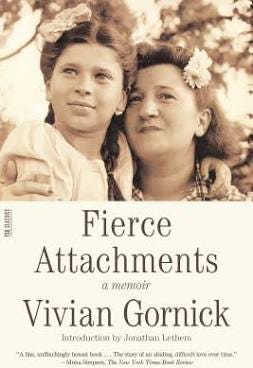

Vivian Gornick sits behind a stately desk (decorated with a framed and occasionally spat-upon picture of her mother) up on the third floor. Gornick is the author of Fierce Attachments, a memoir about growing up in midcentury New York. It features tenements, crazy neighbors, intra-ethnic squabbles. The book’s potential for sounding like the voiceover in a bad nostalgic sitcom (Us kids hated running into old Mrs. Ducker!) seems perilously high.

But Gornick leapfrogs this danger. Fire escapes and laundry lines are what she happens to be looking at, but the point of the book — the delight of it — is the quality of the looking. Plunk her down in North Platte, Nebraska or the Australian bush and she’d write something just as good. She’s a genius at articulating the subtleties of thought and perception that, despite passing mostly unnoticed, determine the air quality of our mental lives.

Look at this smoke-sketch:

A new neighbor moves into the Gornicks’ building. Her name is Nettie. She’s got red hair, almond-shaped eyes. She reminds young Vivian, who immediately falls half in love with this exotic (i.e. non-Jewish) creature, of Greta Garbo.

Part of Nettie’s allure is that she’s temporarily husband-less — he’s in the Merchant Marines. When he does briefly return (“A kind of illumination settled on her skin. Her green almond eyes were speckled with light.”), he beats her up. And just when we think that this is going to be poor Nettie’s story — hiding bruises, avoiding neighbors’ glances — her husband dies. Killed in a bar fight somewhere on the Baltic sea.

And so now Nettie, who had initially been regarded warily by Vivian’s turbine of a mother, is welcomed into the building’s fold. Her beauty no longer unsettles people. She starts coming over to the Gornicks’ every day. Only — have you noticed the men coming and going from Nettie’s apartment? They seemed at first to be mourners — old shipmates of her husband’s — but then they kept coming, looking furtive in the hallways. (Mrs. Gornick is, like her daughter, a first-class noticer).

And so one day Vivian — who doesn’t like to credit all this talk about her beloved neighbor — bursts into Nettie’s apartment. This is no rare thing; the traffic between the Gornicks’ apartment and Nettie’s is free. But on this Saturday Vivian walks in on a peculiar and muted scene. “That morning I saw a tall thin man with straw-colored hair sitting at the kitchen table. Opposite him sat Nettie, her head bent toward the cotton-print tablecloth… Her arm was stretched out, her hand lying quietly on the table. The man’s hand, large and with great bony knuckles on it, covered hers.”

Nettie jumps in her seat, startled by the intrusion. And — “In her eyes was an expression I would see many times in the years ahead but was seeing that day for the first time, and although I had not the language to name it I had the sentience to feel jarred by it. She was calculating the impression this scene was making on me.”

Isn’t that remarkable? Not just as a piece of writing (though that towering first sentence, supported by a single comma, is an impressive feat of mortar-less construction) but as a piece of noticing. It’s a never-ending astonishment to me that a human face and body can silently communicate something as subtle and intricate as: she’s calculating the impression this scene is making on me. Try describing that look!

And yet it’s real, it’s true — it’s the kind of experience we all have every day, but that tends to slip literature’s net (partly, in this case, because of the mental gridlock we experience upon reading anything resembling he knows that I know that he knows). We are, all of us, instruments of astonishing, almost supernatural, sensitivity. He’s worrying about his job. She’s wondering if I noticed that she just glanced at her phone. Most of us register these things subliminally and then skip directly to fretting about their consequences (If he loses his job will we have to move?). Gornick, though, pauses and dilates on the moment of noticing itself — and renders it in prose that has the calm elegance of a balanced equation.

One purpose of writing — part of the mission statement printed on Literature, Inc.’s corporate documents — is to verbalize the whole of experience: to put words to reality’s every nook and cranny so as to reassure each of us skull-encased prisoners that we are not, in fact, alone. Gornick in Fierce Attachments does for certain nuances of perception what Tolstoy did for the battlefield and Joyce did for Dublin. She brings them into literature’s fold. She claims them for herself, and so makes them ours.

This was a lovely review, and, at least for me, a moment of grace in chaotic times.