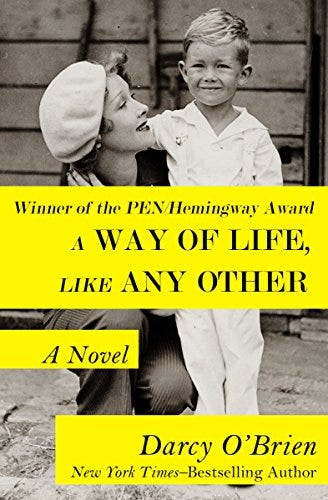

Darcy O'Brien, A Way of Life, Like Any Other

exquisite tedium & marriages in miniature

“‘Would you shut up with your goddamned avocados!’ Maggie would say, and Sterling would be quiet for the rest of the evening, silent in a corner of the couch or at the table, getting up to go to the bathroom three or four times, but moving slowly and carefully, because of his stitches.”

If there were an NFL Combine for comic writers — a grueling multi-day extravaganza during which they were forced to produce witty lines of dialogue while frowning editors clutch stopwatches — the 40-yard dash would be: the speed with which you can launch a character from non-existence into indelibility. In how few lines can you take the reader from having never heard of Aunt Carol to saying Ah yes, how wonderfully like Carol.

The most freakish performance I’ve seen lately in this event (coaches lowering their sunglasses to exchange incredulous stares) was by Darcy O’Brien, in his growing-up-in-Hollywood novel, A Way of Life, Like Any Other. O’Brien snatches a character named Sterling out of the void and sketches him so clearly (he is a dinner-party bore, with a penchant for going on endlessly about his avocado business) that the mere word avocado will, for anyone who’s read the book, provoke a dreamy, grin-suppressing smile. He manages it in under a page.

A Way of Life, Like Any Other is a short, brilliant, memoir-ish novel about a young man’s growing up amidst the movie business in the middle of the twentieth century. I hesitate to use the dread phrase “coming of age” (something critics say when they aren’t close enough to pat an author on the head) but that’s what the novel is. We watch the narrator wriggle out of the choking embrace of his actor parents and into the sexual fever of early adulthood. The book feels like Goodbye, Columbus’s hip Californian cousin.

About those parents: the narrator’s mother, once a star, now lazes around the house, drinking like Lucille Bluth and occasionally making half-hearted gestures in the direction of suicide.

“I couldn’t let you see me like that, with blood soaking the damask and in my hair and in pools on the parquet. You can thank me for that, darling, I love you too much, like a mother.”

She’s the sort of parent who finishes the most wildly inappropriate monologues about her sexual and professional miseries by saying:

“I wonder how many mothers and sons can talk to each other this way. We’re very fortunate.”

She and her husband (a dim, dishonest, John Wayne-type) throw frequent dinner parties, at which the narrator is forced to nod obligingly while the adults talk of movies going over budget and actresses forgetting their lines. One of the regular guests is Maggie, the father’s former agent.

She had a husband, Sterling, who was always recovering from an operation. … Sterling was in the avocado business. He said it was a good business for him to be in because he was sick a lot, and the avocados more or less took care of themselves. All over America people were eating more avocados. He couldn’t get enough of them. They were good for you, much better than a lot of other fruits.

This is the first we hear of Sterling, and already we like him — like that he exists, I mean, in all his promising tedium. That he is always recovering from an operation places us in the all-seeing but half-comprehending vantage of childhood. Adults parade through a child’s life, known by their idiosyncrasies (Was she the one who wore too much perfume?), not yet attached to full biographies.

And his avocados! This was, remember, the 1940s, when guacamole and chips were not yet as ubiquitous in America as bread and butter, so Sterling is essentially your friend who won’t shut up about Orange Theory.

“People should eat two or three avocados a day,” Sterling said. “The Mexicans understand this better than we do. I always know I’m recovering when I can eat avocados again.”

If Sterling were only this — the vehicle for a few marvelously boring lines of dialogue about avocados — it would be enough. There’s a wonderful, Wodehouse-ian straight-facedness to how O’Brien sketches Sterling and then lets him talk and talk. But at the end of Sterling’s monologue (Sterling would probably regard it as the early middle of his monologue), O’Brien writes:

‘Would you shut up with your goddamned avocados!’ Maggie would say, and Sterling would be quiet for the rest of the evening, silent in a corner of the couch or at the table, getting up to go to the bathroom three or four times, but moving slowly and carefully, because of his stitches.

And it’s with this sentence that poor beleaguered Sterling enters the pantheon. There is, first of all, the astringent suddenness with which Maggie steps in as the reader’s proxy, silencing her husband. And then there is the short story of Sterling’s sad acceptance of his fate, embedded in the middle of the sentence, an entire marriage in miniature (quiet for the rest of the evening, silent in a corner).

And then, best of all, there is the return of Sterling’s perpetual wounded-ness, nearly forgotten amidst the hail of avocados.

…moving slowly and carefully, because of his stitches

Slowly and carefully grant Sterling a certain dignity — we feel the pain and silence beneath the blather. And with because of his stitches, O’Brien obeys the trite but nevertheless wise advice that a sentence should end with its funniest words — and he also, more importantly, makes Sterling so intimately real (the damp tenderness of stitches) that our laughter is now edged with compassion. We’re still laughing at Sterling, but that laughter has become sibling laughter, guilty laughter, laughter that erupts the moment the front door is closed. One page ago we had never heard of Sterling. Now we know him well enough to wince sympathetically at the sight of him.

Thank you for this introduction to a book I was not aware of. I'm not certain if I'll read it or not, but I am, at this point, intrigued as always after reading one of your essays.

Hello, I think I discovered you through a NYTimes article (?) back when and am using One Sentence as my book list.

Problem is... can the books ever live up to your wonderful essays?

A Way of Life, Like Any Other reminds me of Diary of a Nobody (1892). Banality was never so hilarious. Maybe you've read it.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1026/1026-h/1026-h.htm